Fit for work? Securing the health of the working-age population

1 Feb 2011

Report by Ben Baumberg, Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion (CASE), LSE

IES’s policy conference, held in November 2010, brought together experts, stakeholders and interested parties to debate issues relating to the health of our working population. Delegates heard contributions from UK experts, including Dame Carol Black, and speakers who set the UK experience in an international context.

Why fitness for work?

Starting from a marginal position in the early 2000s, the health and work agenda has become a central feature of political debate within all of the major political parties. Much of this is driven by the economic cost of ill-health, made up of both the £15-20bn estimated cost of sickness absence and the further cost of disability and incapacity benefits. On a human level, we know that ‘work is good for you’ – but this cannot be just any work, as the evidence suggests poor-quality, low-paid insecure work is as harmful to health as unemployment.

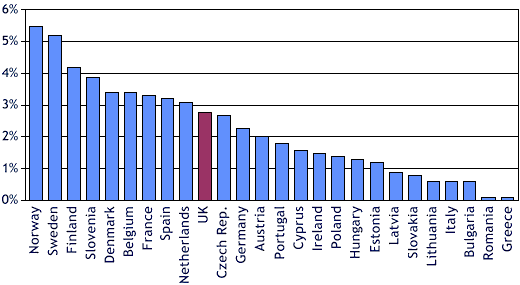

The UK is in a strong position. Compared with other countries, we have a good health and safety record, sickness rates have been improving, and UK workers say that work has less impact on their health than in other countries. Nevertheless, the UK lags behind a number of European countries (see Figure 1 below). But the world of work is changing. While rates of temporary work have been constant, we can expect work intensification; new technologies will provide flexibility while limiting discretion over how to perform our work and blurring boundaries between work and life; and we will see a rising proportion of people with health problems in employment, simply due to population ageing.

Figure 1: Sickness absence rates in the EU

Fitness for work is therefore a major policy concern, and is only likely to become more so in the future. We now know a lot about ‘what works’, particularly for people with musculoskeletal problems. IES’ review for NICE has shown the importance of early intervention by a multidisciplinary team, using caseworkers who are focused on the return-to-work process. We know that working with employers is crucial – particularly SMEs, who are hard to engage. Similarly, GPs have a pivotal role, and the IES evaluation of the new Fit Note will tell us how far we are succeeding in changing GPs’ relationship with the workplace. Yet there is still a lot to learn, and the conference offered an opportunity for us to take stock of existing research, and to focus on what we need to learn.

Where we are now, and where we’re going

It was fitting that Dame Carol Black opened the conference – not just in her role as National Director for Health and Work at the DWP, but because it was the Black Review that catalysed the health and work agenda in 2008. Many factors were identified in the initial review as standing in the way of a healthier working-age population, some of which were cultural (eg, misconceptions about health and work; managerial attitudes), but others that were systemic. The review therefore called for a pathway of care to prevent worklessness, based around early referral to a Fit for Work Service. Many steps have since been made in that direction, including the new Fit Note, the Fit for Work Service pilots, the national standards for OH services, and the challenge fund for SMEs.

Having identified what needs to be done, the challenge now is to make sure that progress is measured and maintained, and that hearts and minds are changed. Carol Black flagged the ‘health at work’ strand of the Public Health Responsibility deal (which brings government, businesses and NGOs together), which is perhaps the first time that a Secretary of State for Health has put work and health as a central pillar in public health policy. This will hopefully be similarly prominent in the upcoming Public Health White Paper. She also described her active involvement in a number of other agendas, including welfare reform, the follow-up to the Macleod review on workplace engagement, and other cross-government collaborations.

However, there are a number of obstacles to be overcome, such as finding funding for the continuation of the Fit for Work Service after April 2011, the need for changed thinking within the occupational health profession, engaging SMEs, and strengthening the evidence on mental health – and not least the rise of obesity, leading to an increasing burden of chronic health conditions in older workers.

Work as a cause of health inequalities

Alongside the Black Review, the other major policy review in recent times is the Marmot Review of Health Inequalities. This review’s discussion of work and health inequalities was presented by its Senior Research Fellow, Professor Peter Goldblatt, who focused on the need to ‘create fair employment and good work for all’ (one of six main policy objectives of the Review). He argued that good work is based on four characteristics: having appropriate income in and out of work; participation in the labour market; avoiding adverse physical/chemical hazards; and a positive psychosocial environment.

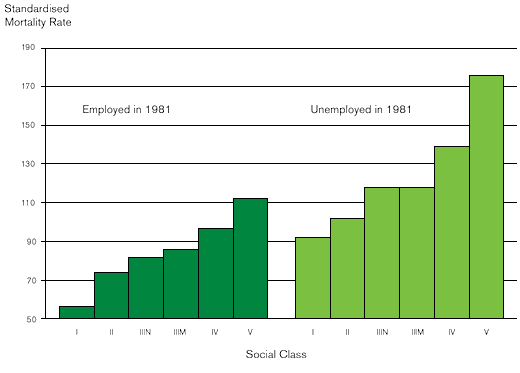

The balance between work in itself and good work can be seen in Figure 2 below, where the health of the unemployed is worse than that of the employed in every social class – but equally, for both the employed and the unemployed, there is a strong social gradient by class. He particularly focused on the psychosocial environment, which can be harmful in four ways: demands-control imbalance (ie, demanding work with little control); effort-reward imbalance (ie, working hard with little reward); organisational injustice; and precarious employment.

The review has already resulted in partnerships with local authorities and regional bodies to develop health inequality strategies; an official response from Government is expected in the future.

Figure 2: Mortality of men in England and Wales in 1981-92, by social class and employment status at the 1981 Census

Source: Office for National Statistics Longitudinal Study

Source: Office for National Statistics Longitudinal StudyLessons from around the world

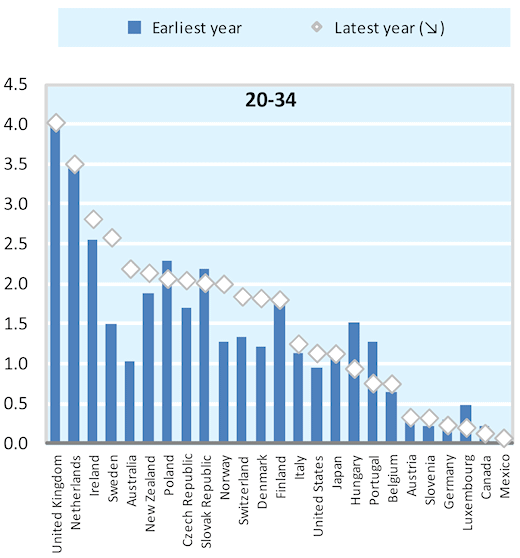

Christopher Prinz, Senior Economist at the OECD, asked what the UK might learn from other high-income countries’ experiences. In many ways the UK is similar to the rest of the OECD: the problem is that employment rates among people with chronic health problems is low, and – combined with a trend away from unemployment benefits towards disability benefits – most countries have seen large rises in the receipt of health-related benefits. Where the UK stands out is in disability benefit rates among young people, which are the highest in the OECD (see Figure 3 below).

Figure 3: Disability benefit recipiency in young people is higher in the UK than anywhere else in the OECD

Source: OECD (Sickness, Disability and Work review)

For all countries, he argued that ‘policy is behind the disability problem, and therefore it is to a large extent policy that can solve the problem again’. There are however three particular lessons for the UK from elsewhere. Firstly, the UK needs better incentives for all actors – including employers (as in the Netherlands), claimants (where the UK has improved), and service providers (as in Switzerland). Secondly, better incentives need to be matched by greater responsibilities – for claimants through activation policies, for employers through occupational health services, and for public authorities to engage earlier. Finally, there is a need for a better assessment system where capacity not incapacity is assessed, and all actors are given the support they need.

This is the culmination of several years of OECD learning – but when it comes to mental health, many questions remain unanswered. Mental ill-health poses special challenges, and accounts for an increasing proportion of disability benefit claims internationally. The OECD has just launched a new project focusing on this, which hopes to tackle this problem through the health system, the transition from school to employment, benefit systems, and the workplace.

The right way to approach ‘active ageing’

Simplistic policies to extend working lives will not work – but coherent active ageing policies can, according to Alan Walker, Professor of Social Gerontology and Director of the New Dynamics of Ageing Programme. By the age of 68 – the proposed new State Pension Age in the UK – 75% of workers cannot expect to be disability-free. Moreover, we know that ill-health will be concentrated among manual workers and the least wealthy. Simple policies to extend working lives are simply not realistic for the vast majority of older workers.

Yet there is considerable variation in labour market participation rates among older workers in the EU – and it is clear that this is not due to different levels of disability, but instead reflects wider structural factors. A true ‘active ageing’ agenda would go far beyond a narrow focus on employment among older workers, instead looking across the lifecourse and using a wide range of policy levers. Among a range of specific policy aims, this includes combating age barriers to work, facilitating flexible retirement, and lifelong learning. ‘Age management’ among employers is crucial here, including job redesign, for which practical tools such as the ‘Work Ability Index’ can help. Extending working lives is therefore possible, but only within a comprehensive active ageing strategy.

Welfare reform and fitness for work

The welfare reform White Paper had been released only days before the conference, and its impact on those with mental health problems was summarised by Roy Sainsbury, Professor of Social Policy and Research Director of SPRU at the University of York. Currently there are 2.3m people with mental health conditions claiming out-of-work benefits in the UK. Those on incapacity benefits have already seen substantial changes in the welfare system, with the introduction of Employment and Support Allowance and the phased rollout of Pathways to Work. However, Pathways’ initial success was followed by later failure (particularly among private sector providers), and staff were uncertain as to how to help those with mental health problems.

We now have the prospect of a ‘new landscape’ in welfare to work. Several means-tested benefits are being rolled-up into the ‘Universal Credit’ that enhances the incentives to work, while the existing support system is being replaced by a network of output-incentivised private providers through the ‘Work Programme’. While much detail remains to be fleshed out, it is likely that large numbers of people with mental health problems will be found ‘fit for work’ and will then claim Job Seeker’s Allowance (JSA), or even not claim any benefits at all, while still seeing themselves as having limited fitness for work. Many will also be on the Work Programme, and if providers are not properly incentivised then they might ‘park’ the hardest-to-help without offering real support. But if we consider the reforms separately from the wider cuts in welfare, people with mental health problems will also have additional opportunities through the simpler benefit system and more transparent incentives to work.

Final thoughts

The conference concluded with a debate between speakers and attendees, led by David Brindle, thePublic Services Editor at the Guardian newspaper. Job redesign and better occupational health systems were seen as critically important – but participants were divided as to whether employers would adopt these if suitably encouraged, or whether incentives and/or compulsion were required. Throughout the day, speakers repeatedly came back to the importance of looking at mental health, where our knowledge base is weaker and the policy puzzles more pronounced. Finally, although there were concerns over the impact of the current recession, most of the speakers were optimistic about the future: ‘work and health’ seems firmly on the policy agenda both in the UK and elsewhere, and we seem to be moving – slowly – in the right di

For more information on this work, please contact Jim Hillage at IES.