Whither Welfare-to-Work? IES policy conference report

1 Feb 2010

Freddie Sumption, Research Officer

With a general election on the horizon, a period of public spending cuts ahead and the effects of the recession putting the UK’s welfare system under increased strain, the fourth IES policy conference provided a timely opportunity to draw together labour market experts to discuss ‘whither goes welfare-to-work?’

How does the UK’s welfare-to-work system compare internationally?

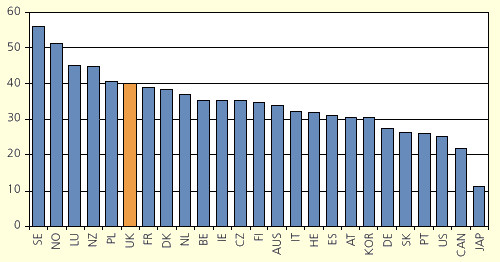

The UK spends considerably less on welfare-towork than most other comparable economies. Around 0.5 per cent of GDP is spent on labour market policies, lower than all but three of the OECD countries. However, much of this resource is channelled into active labour market policies (activities designed to get people back into work) rather than passive policies (such as unemployment benefits), putting it near the top of the scale alongside the Nordic countries and France.

Active LM policy as percentage of total LMP spend (OECD)

Source: OECD

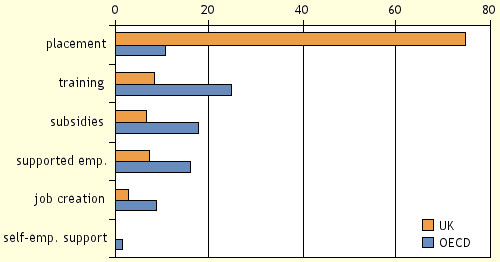

Source: OECDYet the way that this active spend is allocated to different activities looks considerably different in the UK. Here, the emphasis has been on a supply-side ‘work first’ approach prioritising placement activities such as broking, job guidance, and advice and support for job seekers, with benefit sanctions contingent upon participation for almost all claimants since 2008. This has been at the expense of further active labour market policies more prevalent in other countries, such as training and skills development, and demand-side policies such as job creation schemes.

Share of active LMP spend (per cent)

Source: OECD

While this approach has seen some success in the past decade, the recession has introduced new challenges. The unemployment registers are now replete with people able and willing to work, and for whom the unavailability of jobs is the main problem. Periods out of the labour market mean that individuals’ skills are likely to be lost. And the most vulnerable groups – young, low skilled and ethnic minorities – find it even harder to compete for jobs.

In this context, conference speakers and delegates offered answers to some of the following questions:

- What lessons can be learned from previous economic cycles or from abroad?

- How can the UK’s current welfare-to-work system adjust to the changing demands of the labour market through the recession and beyond?

- And looking ahead to years of austerity imposed by cuts in public finances: where does welfare-to-work go from here?

What can we learn from previous recessions?

Dan Finn, Professor of Social Inclusion at the University of Portsmouth and Centre for Economic and Social Inclusion, kicked off the debate by examining the impact of previous recessions on the labour market as well as the policies that were introduced, and the extent to which these were effective or produced unintended consequences.

In particular, he warned that previous recessions have resulted in poor matching as unemployed people are encouraged to take the first job that is available. This can result in a loss of skills, exacerbating structural changes in the labour market later, and a return to inactivity in the long term. One challenge for the government therefore will be to ensure that active labour market policies promote an appropriate balance of activities alongside placement, including access to skills, work experience and post-employment support.

Further, he cautioned that the government’s tendency to target resources towards longterm unemployment in and after recession can make it difficult for the recurrently unemployed – those who flow between unemployment and the labour market – to access the help they need. These individuals, mainly young people with no or few qualifications and on whom recession already has a disproportionate impact, are then in particular danger of becoming disengaged and falling into long-term unemployment. Whilst recognising the increased pressure on welfare resources in recession, government should therefore ensure that the policy agenda is not diverted away from this group.

What can we learn from abroad?

David Grubb, Senior Economist at the OECD, spoke about the effectiveness of welfare-towork policies in other OECD countries within and outside recession, and the extent to which these might be applicable to a UK agenda. He commented that, in general, countries with a high ratio of active to passive policies tend to fare better in a recession and experience a smaller growth in unemployment than those which increase benefits without activation measures, such as Spain and the US. However, he warned that recession can weaken the effectiveness of active policies, since the extra pressure on the system dilutes the personal attention each jobseeker receives, making it possible to spend longer periods passively on benefit. Further, over-rigorous placement programmes, such as those that force individuals to accept the first available job, may not be the answer. While they may decrease unemployment in the short term, individuals who are pushed into jobs for which they are poorly suited and those who are ‘threatened’ into activity are likely to return to unemployment later.

In terms of the delivery of welfare programmes, he drew on evidence from Belgium and Switzerland to make the case for partial decentralisation, rather than national management or full decentralisation. Such policies work best where there is national responsibility for strategic management and legislation, but regional authorities manage the benefits and are responsible for the implementation of individual programmes.

Paul Gregg, Professor of Economics at Bristol University, also drew on evidence from abroad to support his recommendations to the government (outlined in the 2008 Gregg Review and due to come into effect in 2020-2011) for increased personalisation of work-focused services for those with barriers to working.

Based on the Norwegian and Dutch models of increasingly personalised services for harder to help groups, he promotes the introduction of a three-part model whereby all benefit recipients would be split into one of three groups, regardless of the benefit they are receiving:

- Work-ready group: those who are able to look for employment with little support.

- Progression to work group: those for whom a return to work would be possible in the long-term with some support (such as lone parents and those previously on incapacity benefit).

- No conditionality group: those for whom a return to work is not currently appropriate.

For the ‘new’ middle group, the pathway should be highly flexible, allowing the individual and their adviser to design a personal programme of work-focused activities, tailored to their capability and designed around their circumstances. This may include addressing confidence or health problems, undertaking training, work-focused interviews or work-related activity. Support would be available immediately and not contingent on time spent on state benefits for people who are out of work.

What would welfare-to-work look like under a Conservative government?

Panel discussion with Nick Timmins, David Freud,

David Grubb, Paul Gregg and Dan Finn

Keynote Speaker David Freud, Nominated Shadow Minister for welfare reform, set out what the Conservatives perceive to be the main challenges facing the welfare-to-work system in and beyond recession, and how the party’s plans for welfare reform would tackle these issues.

Firstly, he highlighted the need to get a substantial proportion of economically inactive people back into the workforce. To do this, the party proposes to replace the Flexible New Deal (FND) with the ‘work programme’, under which everyone on out-of-work benefits or support for lone parents would be referred to a single programme after six months, as opposed to a year, as is currently the case. Defending this move, he claimed that the distinction between different groups of claimants is artificial; all groups are unemployed yet work-capable and would therefore benefit from similar support.

Secondly, in order to tackle the issue of cyclical unemployment, providers would receive incentives to secure sustainable employment for clients, with the final instalment being received after a year, rather than six months under the current scheme. Further, Treasury rules would be changed to enable providers to use the benefits saved once someone has a job.

Lord Freud also set out proposals to tackle youth unemployment and disengagement through increasing apprenticeships and introducing work pairing, whereby young people who are disenchanted with education would be paired up with a sole trader for six months. Funding for this element would come from the government’s Train to Gain scheme, which is due to be scrapped in its current form.

Final thoughts

Although the depth of the recession and its full impact on the labour market remains to be seen, there was cautious optimism that the UK has been able to withstand the unemployment spikes of previous recessions, and that our active placement programmes may have been instrumental in this respect. However, there may be a case to reconsider the nature and balance of programmes during and after recession, in order to ensure that those out of work are being appropriately supported and not simply being placed into jobs for which they are poorly matched and from which they are likely to ‘rebound’ later.

In particular, several speakers and delegates expressed concern about the absence of tailored support for harder to help groups, which will be essential in ensuring that these individuals are not further marginalised, and to meet targets for decreasing the economically inactive population.

These will certainly be complex challenges for policy-makers after the general election which, whether or not it results in a change of government, is likely to be followed by significant cuts in public spending.

For more information on this work, please contact Jim Hillage at IES.