Labour Market Statistics, February 2026

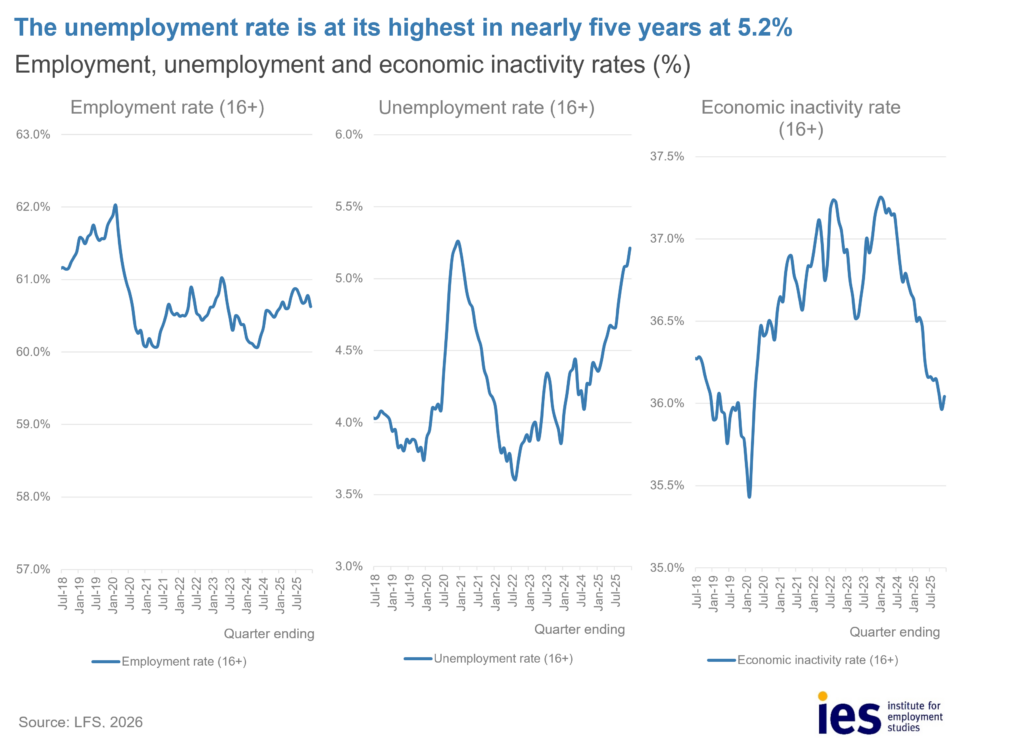

Unemployment is close to a five-year high at 5.2%, as more people are actively looking for work, with the employment rate and economic inactivity rate down slightly on the quarter. Payrolled employment continues to fall, though seemingly at a slower rate.

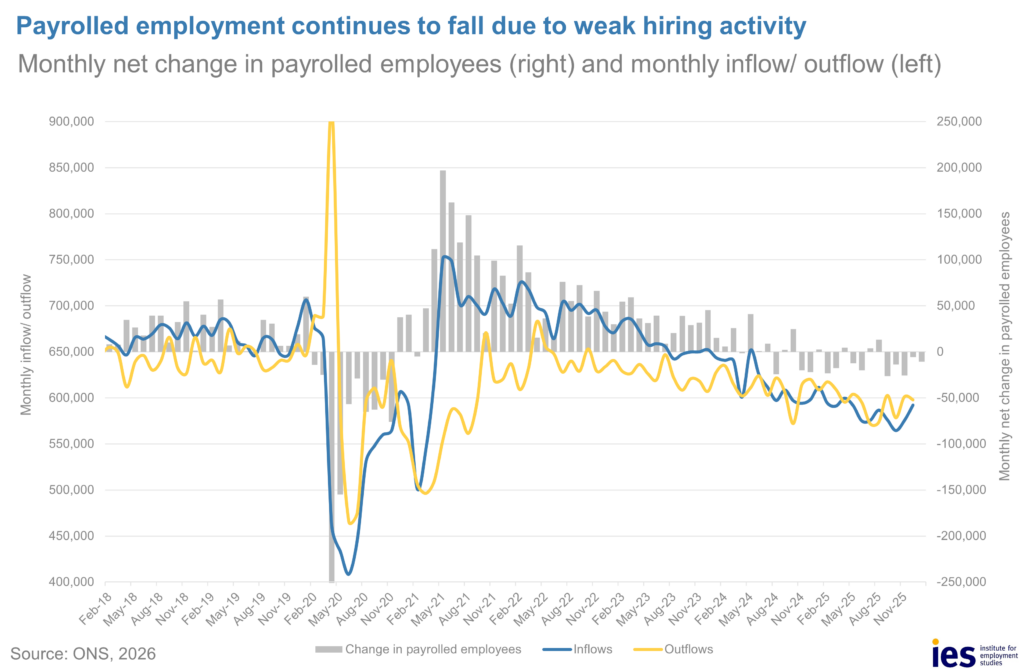

Early estimates from December have been revised down to a fall of 5,700, and early estimates for January indicate a fall of 10,600. Payrolled employment has fallen for 10 of the last 14 months. Prior to this, excluding the pandemic, payrolled employment fell in seven of 113 months over the last decade. Retail and hospitality have seen the largest falls, with over 120,000 fewer jobs compared January 2025. Inflows on to payrolled employment are 16% lower compared to pre-pandemic, reflecting the slowdown in hiring.

Early estimates from December have been revised down to a fall of 5,700, and early estimates for January indicate a fall of 10,600. Payrolled employment has fallen for 10 of the last 14 months. Prior to this, excluding the pandemic, payrolled employment fell in seven of 113 months over the last decade. Retail and hospitality have seen the largest falls, with over 120,000 fewer jobs compared January 2025. Inflows on to payrolled employment are 16% lower compared to pre-pandemic, reflecting the slowdown in hiring.

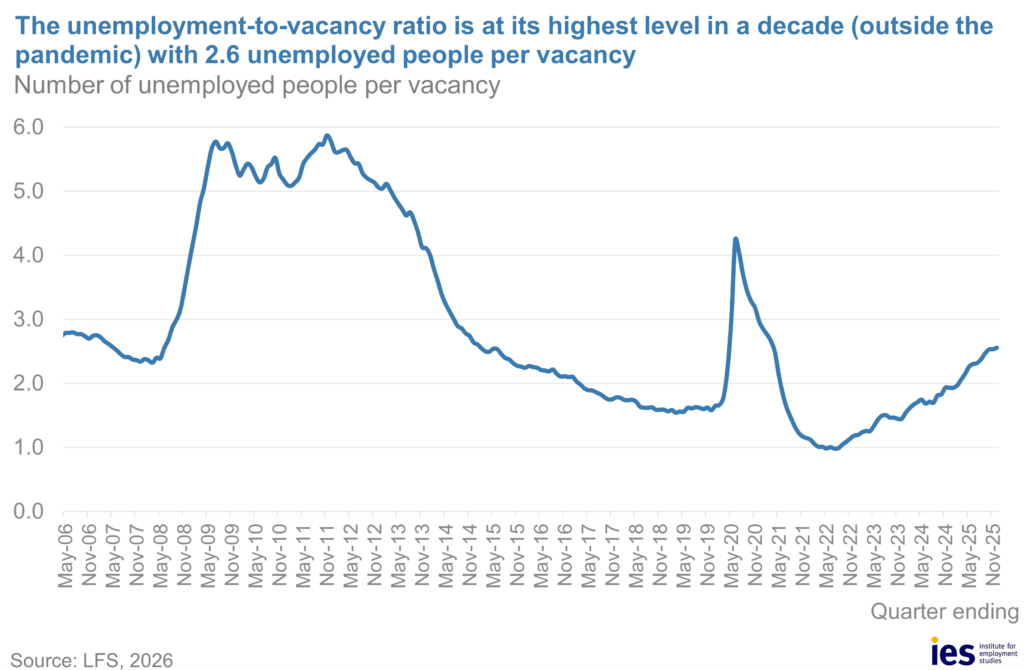

Vacancies appear to have stabilised, with a slight increase of 2,000 over the last quarter. The largest falls were in health and social care and hospitality, while the largest increases were in manufacturing and transport.

Rising unemployment and weak hiring means that there are more people looking for fewer jobs and, outside the pandemic, the unemployment-to-vacancy ratio is the highest in 10 years, with 2.6 unemployed people per vacancy. There are a further 2.1 million people who are outside the labour force who want to work. Combining the two, there are 5.4 people either looking for work (unemployed) or wanting to work but not actively looking (economically inactive) per vacancy – again the highest ratio outside the pandemic.

Pay growth has also slowed, particularly in the private sector. Annual pay growth in the private sector is the lowest it has been since the pandemic. While inflation is falling, it continues to erode the impact of nominal wage increases, with real annual regular pay growth at 0.5% in December 2025. This means workers are only marginally better off than they were a year ago.

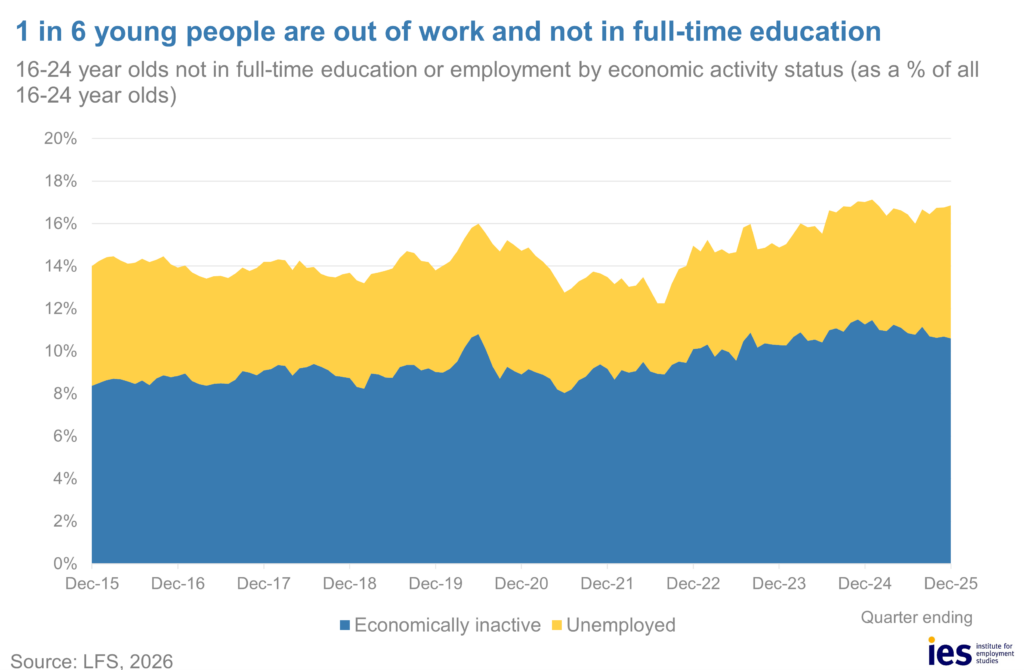

The youth unemployment rate continues to climb and is at its highest rate in more than 10 years, including the pandemic, at 16.1%, as young people have been affected by the slowdown in hiring. Nearly 40% of unemployed young people (18–24-year-olds) have been unemployed for more than 6 months and 1 in 4 young men who are looking for work have been unemployed for more than a year. In addition, a relatively high proportion of young people are economically inactive (many due to long-term sickness), meaning that the employment rate for 16–24-year-olds not in full-time education is the lowest it has been in 10 years (including during the pandemic).

Recent labour market trends are reinforcing existing inequalities. The North East and the West Midlands – regions with lower employment rates – have seen the largest falls in employment over the last year. The disability employment gap is also widening, as employment rates for disabled people have fallen by 1.2 percentage points compared to 0.1 points for non-disabled people. Data suggests that there has been a sharp rise in unemployment rates for disabled people with nearly 1 in 10 (9%) actively seeking work – more than two times the unemployment rate for non-disabled people.

The government needs to work with employers to boost jobs and encourage hiring, while expanding support for people to find work and supporting employers to adopt more inclusive recruitment and employment practices.

Any views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Institute as a whole.