Thanks for the good news Chancellor, but what about youth unemployment?

19 Mar 2015

Jim Hillage and Becci Newton

It was either a coincidence or careful planning that the monthly labour market statistics came out on the day of the Budget. It enabled the Chancellor to underline the dramatic improvement in the labour market in recent years, with record levels of employment and overall unemployment down to almost pre-recession levels. However, not all is rosy in the labour market garden.

Youth unemployment, although down, is still a major, and indeed growing, concern. The youth unemployment rate is almost three times the adult rate and four out of ten unemployed people are aged under 25. At the entry level at least, the labour market is far from fixed. Despite a range of much-heralded initiatives to tackle youth unemployment over the last five years, the youth unemployment rate is higher than it was when the Government took office. Against this backdrop, it could have been expected that the Budget would contain some new measures to address the problem. In the event, youth unemployment is hardly mentioned in the Budget Statement at all. Cynics might think that this may be related to the fact that young people are among the least likely to vote in the forthcoming General Election. However, youth unemployment is a problem that affects us all.

The problem

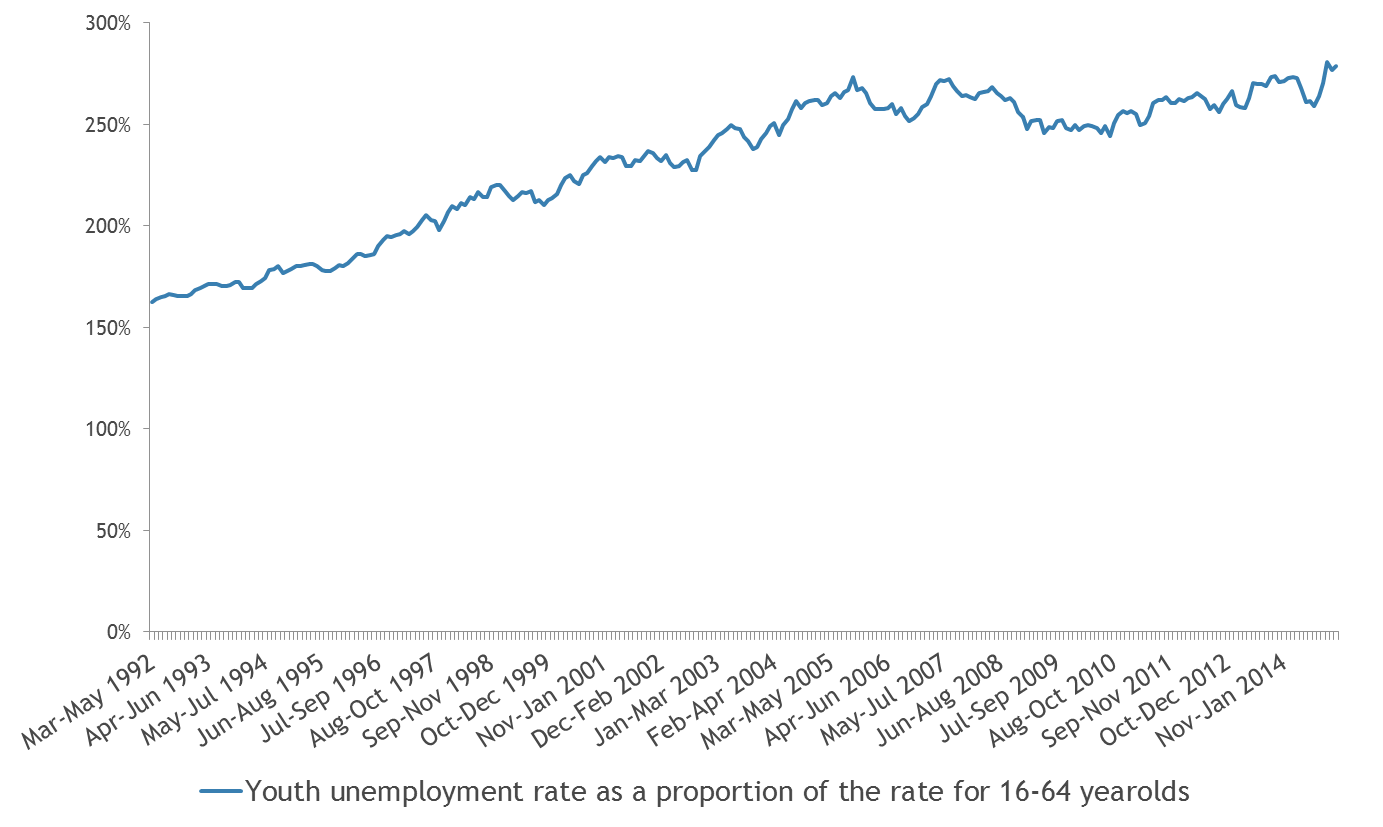

Young people always have found it difficult to find work, relative to older people and the youth unemployment rate is traditionally higher than the overall rate. The problem is that it is getting harder not easier. In the early 1990’s, the unemployment rate for 16 to 24 year olds was one–and-a-half times higher than that for all 16 to 64 year olds, and grew to twice as high by the turn of the millennium. In the mid 2000’s, the youth unemployment rate was 2.5 times the rate of the whole workforce and has recently reached 2.8 times. It is now as high as it has ever been (see Chart 1).

Thus, while youth unemployment fluctuates with the overall state of the labour market and has fallen alongside the adult rate in recent months, it is not falling as fast and the proportion of the unemployed aged 16-24 is starting to grow, now reaching over 40 per cent.

Chart 1: Youth unemployment rate as a proportion of the rate for 16-64 year olds

Source: ONS Labour Market Statistics, March 2015

Young people are struggling to compete with older job-seekers. When asked about their recent experience of recruiting young people, most employers thought their young candidates were reasonably well prepared. However, a substantial proportion felt that young people lacked the skills or experience (or both) that they were looking for. Other concerns included the quality of the young person’s application or their general attitude to work (see Chart 2).

Chart 2: Reasons why some recruiting employers do not recruit young people

Source: (2014) Employers Skills Survey 2013, Evidence Report 81, UKCES

It is not just skills and experience that can hold young people back. Research that IES has done focusing on young people not in education, employment or training (so-called NEETs) highlights the multiple problems that some have including: low socio-economic status, bullying at school, exclusion and absenteeism, low attainment, special educational needs, disabilities and poor mental health, low levels or a lack of parental support, being in care or a young carer, crime or deviant behaviour, and teenage pregnancy.

Young people also tend to have an unrealistic view of the labour market and often apply for or hold out for jobs they have little chance of getting.

Why does it matter?

The ‘scarring effects’ of long-term unemployment among young people are well known, with a sustained period of being NEET at a younger age associated with lower lifetime employment, earnings and general life chances. Successful intervention at an early age can therefore produce long-term paybacks for young people and society as a whole.

The solution

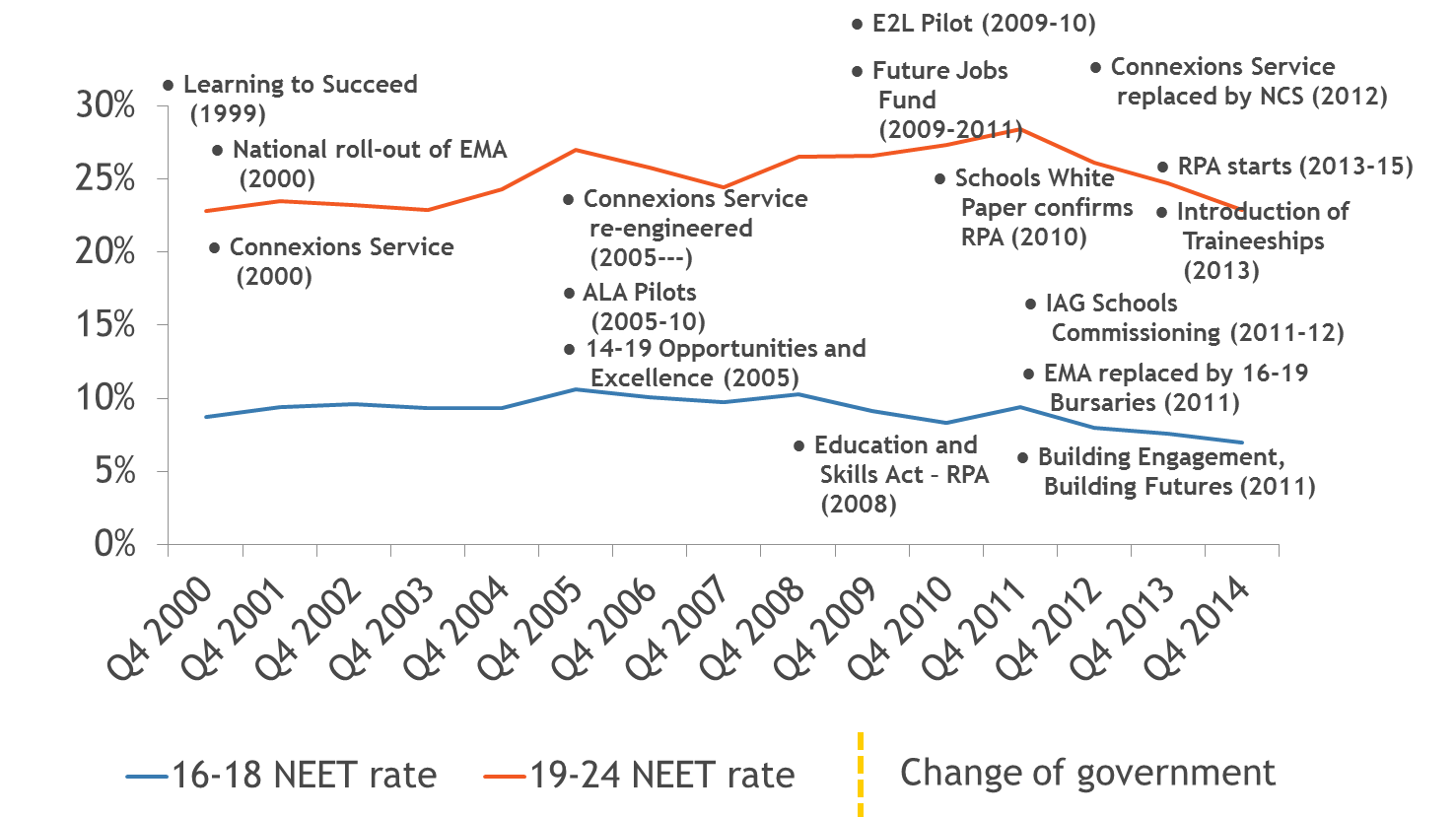

Chart 3: Policy response to youth unemployment

Source: IES 2015

Chart 3 illustrates that there have been plenty of initiatives over the past decade to help young people NEET into work or training. The Labour government launched the Future Jobs Fund which provided young people with a subsidised temporary job. It provided ‘an impressive level’ of sustained job outcomes and, although it cost the Exchequer £3,100 a job, it achieved a social return of over twice that amount[1]. However, it was scrapped by the incoming coalition government after the election.

Most recently, the coalition government launched the Youth Contract in 2012 and Traineeships in 2013. Aspects of the Youth Contract have been effective but the period of active funding is about to cease and there will be no new entrants after the end of March[2]. Traineeships may provide a pathway to apprenticeships and other options, though delivery is small in scale and it is unknown how far they lead to sustained employment and training positions. There are also a range of local initiatives funded through local authorities, working in conjunction with Jobcentre Plus and/or the European Social Fund, again with varying degrees of success. However, the current policy response is piecemeal, confusing (with duplicating initiatives from multiple providers) and, perhaps most importantly, lacks sustained funding.

Nevertheless, the evaluation evidence, from IES and others, does identify some of the key ingredients of a successful approach:

- Interlocking support – to avoid duplication and target the available resource at those young people most in need in a consistent and sustained way.

- A key worker with a dual focus – breaking down the barriers young people face, increasing their labour market awareness and mapping out options – plus an understanding that learning and skill development may follow once a job entry has been achieved.

- A focus on advancement – to avoid young people churning between insecure and low quality work – which involves helping young people make transitions between jobs and finding ways for them to improve their skills

- Flexible training provision – to provide opportunities for young people to build skills both in and out of work.

- Underpinning support to help young people lacking core skills, eg English, maths and employability - all of which are demonstrated to increase young people chances of employment success.

The key problem is that such support costs money. In a climate of limited public spending, likely to continue if not worsen after the election, it will be interesting to see the priority that tackling youth unemployment is given in the forthcoming party manifestos. However it looks like the problem will not go away on its own and whatever the colour (or colours) of the next government the ministers in charge of employment and skills will still have to face up to the persistent problem of youth unemployment.

[1] Fishwick T, Lane P and Gardiner L Future Jobs Fund: an independent national evaluation, Centre for Economic and Social Inclusion, July 2011, Bewley H ‘Impacts and Costs and Benefits of the Future Jobs Fund, DWP, November 2011

[2] Newton B, Speckesser S, Nafilyan V, Maguire S, Devins D, Bickerstaffe T The Youth Contract for 16-17 year olds not in education, employment or training evaluation, , Research Report , Department for Education, Jun 2014