Is there a mental health 'time-bomb' ticking away in the public sector?

1 Jun 2017

Stephen Bevan, Head of HR Research Development

Stephen Bevan, Head of HR Research Development

Mental health at work is in the headlines again. This time, a survey by Mind is shining a light on some of the differences between workers in the public and private sector. Their survey of 12,000 UK employees across a number of industries shows, among other things, that the prevalence of mental illness appears higher in the public sector and that, while more public sector workers feel confident to disclose their problems to their employer, support for those who do speak up is poorer than in the private sector. In fact, fewer than half (49 per cent)of those in the public sector who disclosed mental health problems felt supported, compared with 61 per cent in the private sector. So this report raises some fundamental questions about the health of the public sector workforce and how it is being managed.

First, it suggests that raising awareness of mental illness at work and efforts to reduce stigma are probably not enough if employers are not geared up to both listen and take serious steps to support people who summon up the courage to disclose. One of the risks here is that it will put off some people who are inclined to disclose, driving some mental health problems back ‘underground’ again, which would be a retrograde step. The irony is that there are now more sources of information and support which employers can draw upon than ever before. Mind themselves have some excellent advice and resources on this, as do Remploy and the Mental Health Foundation. We need to do more to boost the number of employers – across all sectors – which have access to this kind of support, even if it just means that they can refer people on to other experts who can help them.

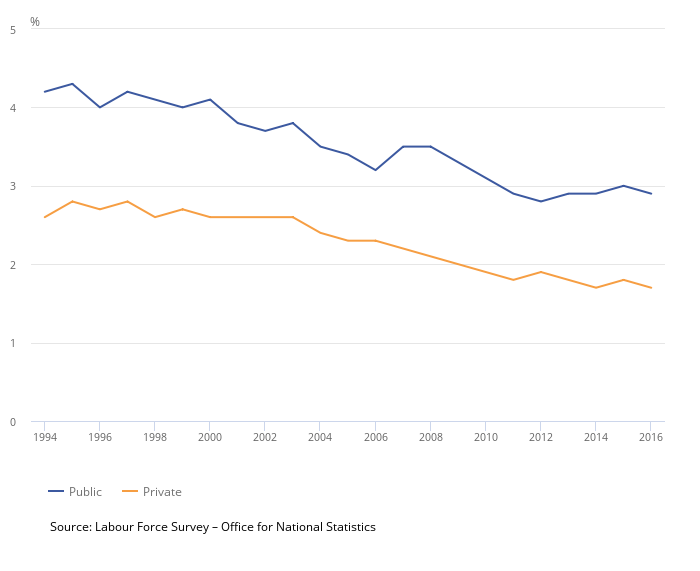

Second, the Mind study reignites an old debate about why there seems to so many differences in the nature and extent of ill-health and sickness absence between the public and private sectors. It is true, of course, that the headline rate of absence has historically been higher in the public sector. The graph below using ONS data shows that this has been the case for many years, although rates of sickness absence have been in decline across all sectors since the mid-1990s.

Sickness absence rate: by public and private sector, UK, 1994 to 2016

The higher rate of public sector absence has given rise to considerable ‘workers vs shirkers’ indignation among some commentators over the years, but close scrutiny of the data suggests that the picture is not that clear cut. For example, the different demographics of the public and private sector workforce helps explain some of the gap . The public sector employs a large number of women in poorly paid jobs, with poorer than average general health. Many are susceptible to short-term childcare and eldercare problems and they are more dependent on public transport than the average person. Despite employment rights allowing unpaid family and emergency leave, the low paid find it more difficult to take time off to deal with domestic crises. For many, sick leave is the only option. Another factor may be the is elevated health risks intrinsic so some public sector jobs. Thus, compared with the private sector, many public sector workers are at higher risk of illness or injury through their work. Levels of back injury, needlestick injury, cross-infection from patients, and physical and verbal abuse are significantly higher among NHS workers than for other workers. Occupational risks among police officers, firefighters and prison officers also inflate the public sector absence figures. Workers in health and social care, for example, are twice as likely to suffer from stress and depression. This has increased the number of days lost through long-term illness. It should also be remembered that 53% of public sector workers take no sickness absence at all, a slightly lower number than in the private sector.

Here at IES we have been carrying out reviews of mental health and sickness absence in the public sector since the 1990s, and most recently in projects with the Police Federation of England and Wales and in our evaluations of the Mind ‘Blue Light’ programme to look at mental health support among people working in the emergency services. What this work tells us is that prevention, early intervention and quick referral to appropriate support is the best way to ensure that mental health problems do not get worse and turn short periods of absence into longer bouts of absence from which it can be much more difficult to return. Part of the answer here is to help line managers to spot the early signs of depression and anxiety. A recent IES webinar looked in more detail at how this can be done.

If the results of the Mind study are representative of what is happening across the public sector then we must redouble our efforts – not just to make it safe for employees to disclose that they have a mental health problem – but to put in place the support they need to stay in or return quickly to work.

Any views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Institute as a whole.