Report summary: Tackling Poor Performance

Poor performance is an issue that worries managers and employees alike. It is of concern to senior managers because it is a measure of how effectively the organisation is led. But people in organisations do not always feel their organisation tackles poor performance appropriately – a hard nut to crack. Dealing with poor performance is an emotive issue. It is perhaps not surprising, therefore, that many organisations fail to address it. In our research, seven large employers shared their perspectives on the issue.

Why tackle poor performance?

Research evidence shows that:

- tackling poor performance is still fairly low on the agenda for employers

- poor performance reduces productivity

- managers find it uncomfortable and would rather ignore it

- it has a negative impact on other staff motivation and retention.

What do we mean by poor performance?

Among the seven employers participating in our study, interpretation seemed to be influenced by what was going on in their business at the time and this was what had prompted a review of their approach. But managers were quick in thinking of individuals, coming up with colourful labels stemming from behaviours such as attitude and lateness. So organisations may have a vague idea of what they mean by poor performance, but people can quickly acquire a poor performer label. A ‘worker with attitude’ may be trendy in certain circles, but if it is the wrong attitude, seen in lack of co-operation with colleagues, it may lead to the employee being removed.

What is true poor performance?

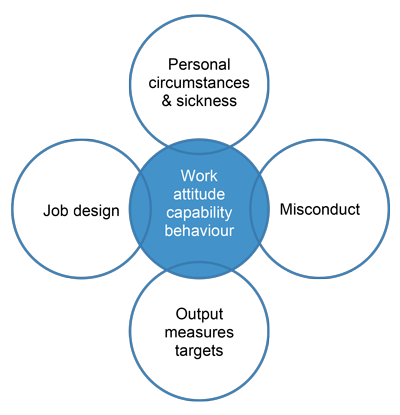

Source: IES

When is poor performance real anyway? Our diagram shows the aspects that can be associated with performance. What could be construed as true poor performance may be small indeed, when we take account of other ways poor performance might be defined. However, the picture is quite confused when we consider that poor performance can result from role overload or unclear objectives or unrealistic targets. Changes to the work environment would probably raise the level of performance.

On the other hand, absence (which can again be seen as a sign of poor performance) or a personal or a domestic problem, may be better handled by Occupational Health. Perhaps the clearest boundary in the picture is the overlap between behaviour and attitude, with misconduct. If the employee is dishonest and unethical, there are strong reasons for invoking the disciplinary process and ultimately exit. Poor performance is legally defined as ‘when an employee’s behaviour or performance might fall below the required standard’. Dealing with poor performance is, however, a legal minefield. This might explain why some employers tend to confuse poor performance with negligence, incapacity or misconduct.

What is acceptable performance?

Employees need to know what constitutes an acceptable level of performance, below which their organisation will consider their performance wanting. This is not so easy when we look at the variety of messages that they may receive from their employers about performance requirements. Given that these often conflict, it may be difficult for an individual to have a clear view of what is meant by acceptable. The onus is, therefore, on line managers to instil some much-needed clarity, and on both parties to agree a standard of performance as well as the targets to be delivered.

Much emphasis was given by our employers to address performance issues informally and as soon as they arose – and most likely outside the performance appraisal process. This was often referred to by the managers we interviewed as ‘micromanaging’ (eg setting clear expectations and monitoring progress). Since the outputs achieved are key, failure to achieve them would obviously be a signal for investigating the level of performance further.

To this end, most of the HR managers interviewed said they ‘would turn to the list of objectives set as the cornerstone for measuring poor performance’. It is therefore debatable as to whether this does not form part of an effective performance review process in the first place. To confuse us further, there are also many ways that employers in the study measured employees’ level of performance to assess whether it is good or bad. All our employers were using both hard and soft measures and differed in the ways they sought these measures, how they combined them to obtain a rating, and in what kind of benchmark they used. Competency frameworks can be useful to spell out unequivocally the actions that are not helpful to the business.

But is the employee poor or simply not the best? Employers judged this with the controversial concept of forced ranking – whether the performance is relative (eg compared to best performers) or absolute (eg against a standard). The process of standard monitoring or calibration, that most adopted to ensure the consistency, and fairness of the overall rating, may serve to assuage employees somewhat, given the universal dislike of forced ranking and organisational league tables. Crossing the line below acceptable performance may involve employees lacking capability or displaying inappropriate behaviour. Crossing the line presents a rather complex picture – the grey areas:

- What makes a good day’s work?

- Are culturally-defined behaviours involved?

- Is the employee in control and willing?

Tackling poor performance

All employers participating would review their selection process to avoid recruiting poor performers in the first place. But organisations need to put in place an overall approach and procedure to deal with poor performance. Approaches we encountered take on two important, but diametrically opposed, dimensions:

- whether the organisation's ultimate aim was to improve performance or remove the employee

- the degree of formality of the procedure used to achieve this aim.

Some organisations adopted a developmental approach, believing that employees’ performance could be improved. Their intervention therefore included a sharper focus on training and development. In this case, a varying degree of formality of the process used was also in evidence. Towards the more formal end of the procedure, but still with an improvement emphasis, we found the approach that a manufacturing organisation had developed, ending in a performance improvement plan. At the other end of the spectrum lies the approach adopted by an electronics company that believed in informally matching people to roles according to their strengths.

We found no evidence of employers using the ‘getting rid of bottom 10 per cent’ approach. But pressure to move towards such an approach could be sensed. A central government agency, for example, used an assessment centre to review the capability of its senior managers. Either explicit (or implicit) the list of poor performers seemed ubiquitous. But poor performance needs to be destigmatised and regularly talked about in a sensitive way. The capability procedure is also the means to document performance issues, which is the key to being able to act. However, evidence also needs to be collected earlier on as part of the appraisal process. Most organisations should clearly spell out the link or the difference between their capability and disciplinary procedures, as the boundary is often blurred.

The most common message emerging from the study is the need for managers to deal with issues early rather than let them get worse. We would like to offer them the following mnemonic as an illustration of good practice. In most cases, dealing with poor performance is a bit like turning on the taps:

| Turning on the TAPS | |

| T | timely and early |

| A | appropriate management style and response |

| P | keep it private |

| S | make it specific to performance, and factual |

Source: IES

The strategic choices

Employers need to decide what they are really trying to do with poor performance.

- Weeding out small numbers has a big impact on the rest of the workforce, giving the message that the organisation is serious about tackling poor performance.

- Losing the worst, keeping the best is clearly in vogue in the United States. This is about ratcheting up organisational performance by getting rid of the lowest performers (often average rather than poor). It can be legally difficult to defend and is disliked by employees.

- Improving performance may be better conceived as re-energising people and improving their skills and communication. This approach works if organisations adopt a collaborative approach, where senior managers work with colleagues to support the line to maximise contribution.

The report

Tackling Poor Performance, Strebler M, Report 406, Institute for Employment Studies, 2004

Hard copy: £19.95. PDF Download: £free