Labour Market Statistics, January 2026

20 Jan 2026

Naomi Clayton, Chief Executive Officer

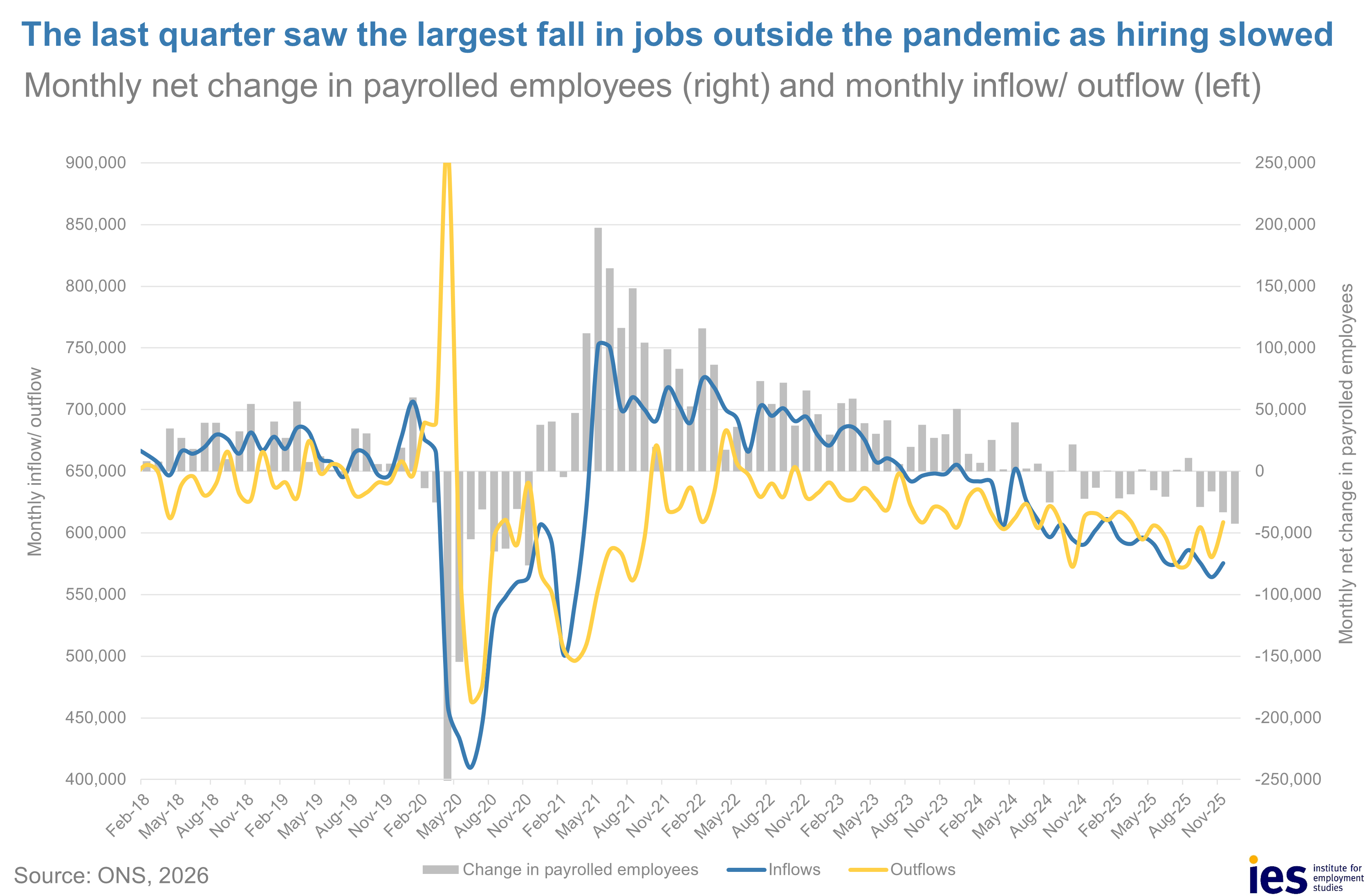

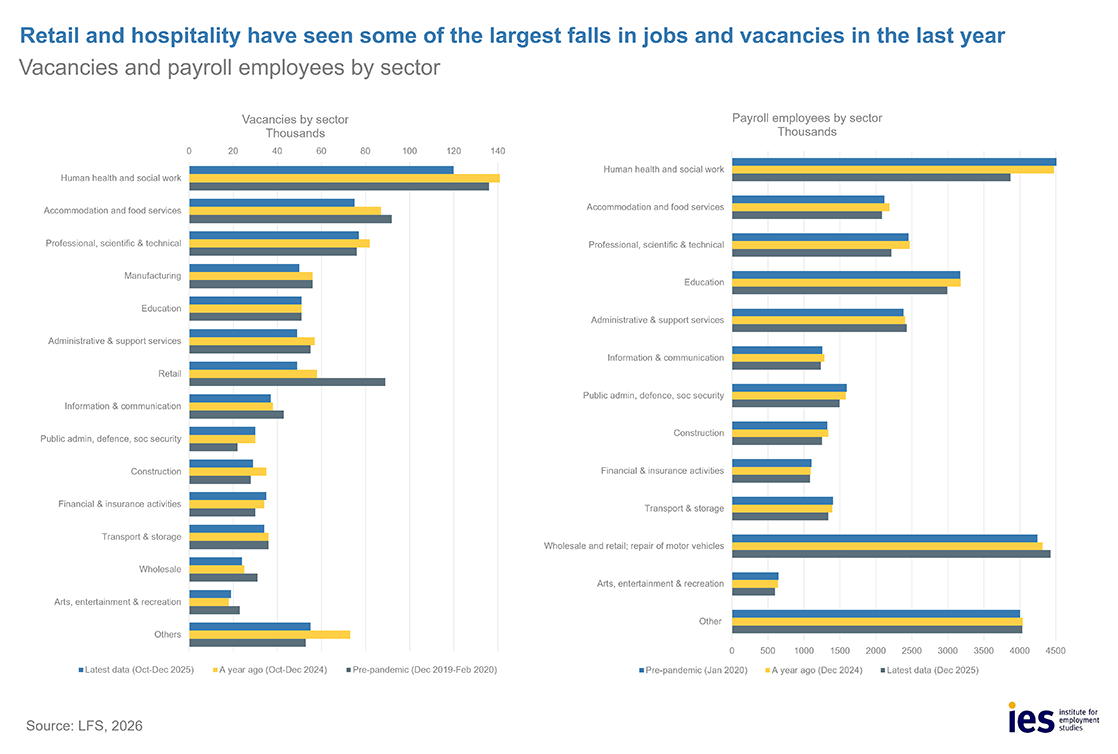

Payrolled employment has fallen by over 90,000 in the last quarter – the largest fall outside the pandemic. This includes early estimates (subject to revision) which indicate that payroll employment fell by 42,500 in December. Retail and hospitality have seen the largest falls, with payrolled employment falling by 37,000 and 20,000 over the last quarter, respectively.

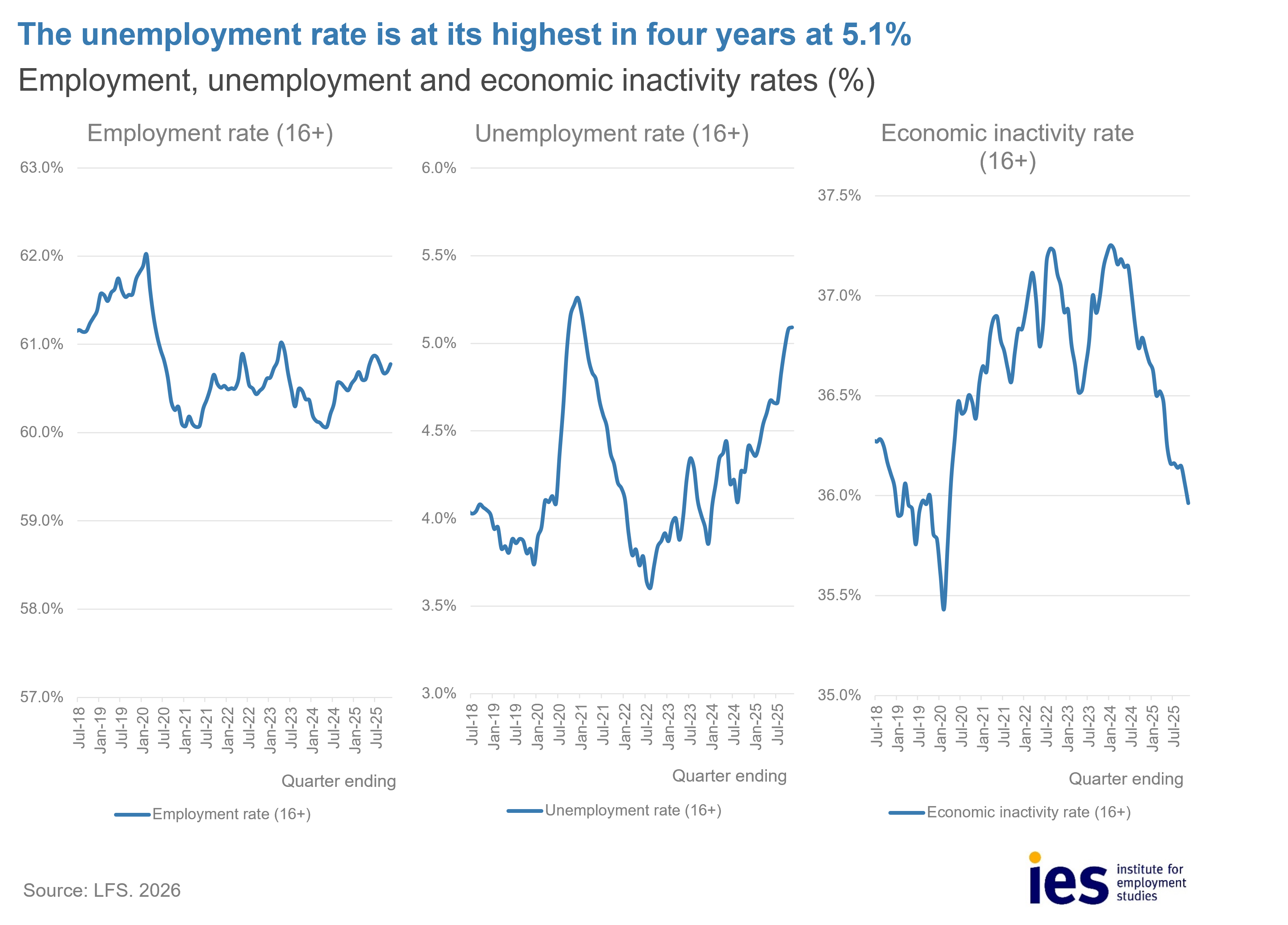

The unemployment rate remains at 5.1% and is up on the quarter and year. This is the highest rate in the last four years and not far off the pandemic peak of 5.3%. The employment rate is largely unchanged on the quarter and up slightly on the year. While the economic inactivity rate is down on the quarter and year, there are still 2.1 million people who are outside the labour force who want to work.

Vacancies appear to have stabilised, with a small increase (10,000) over the last quarter. The largest falls were in health and social care and retail, while the largest increases were in arts and entertainment and transport.

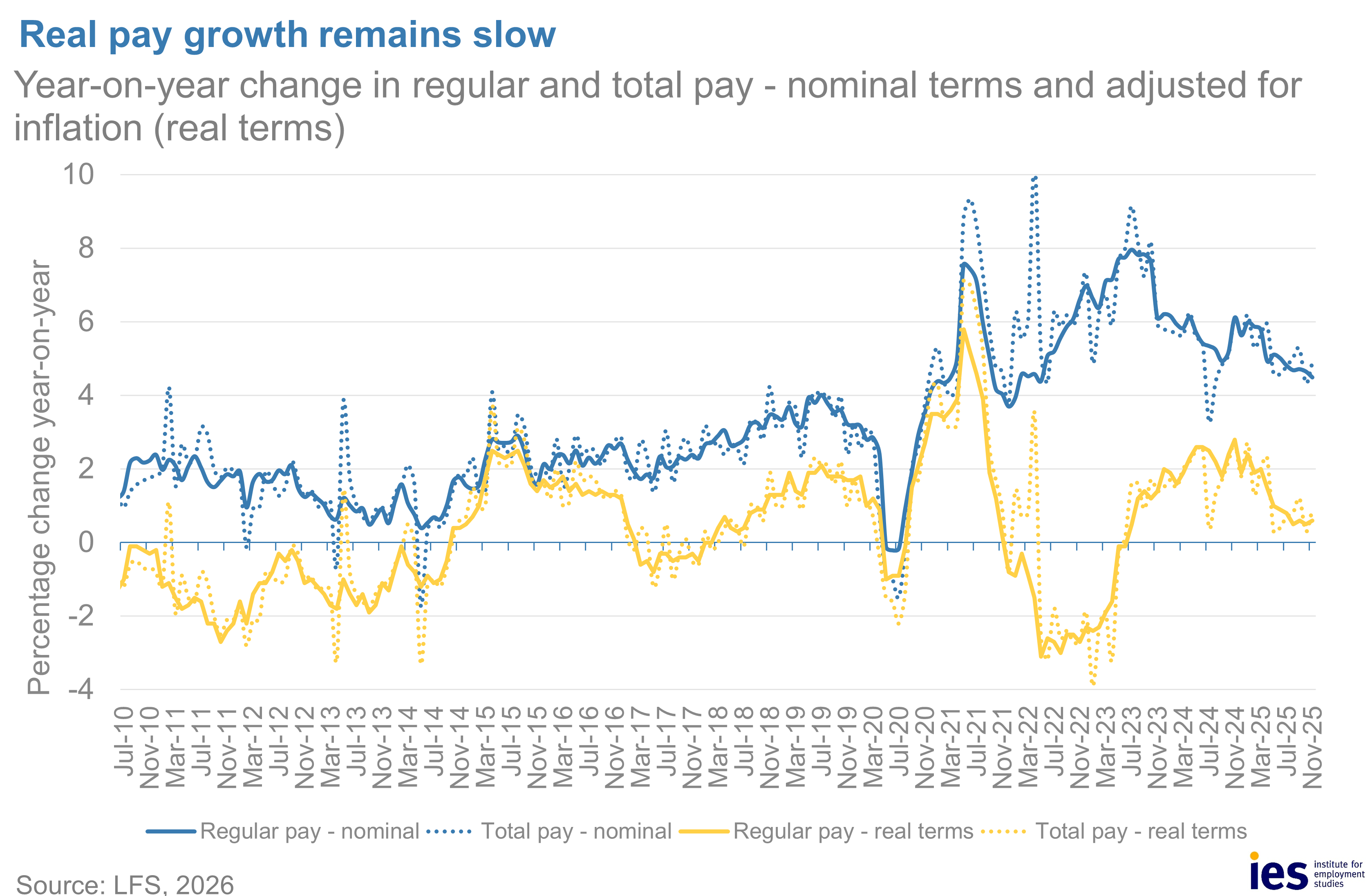

Real pay growth remains weak, particularly in the private sector. Inflation continues to erode the impact of nominal wage increases, with real annual regular pay growth at 0.6% in November 2025 – meaning that workers are only marginally better off than they were a year ago.

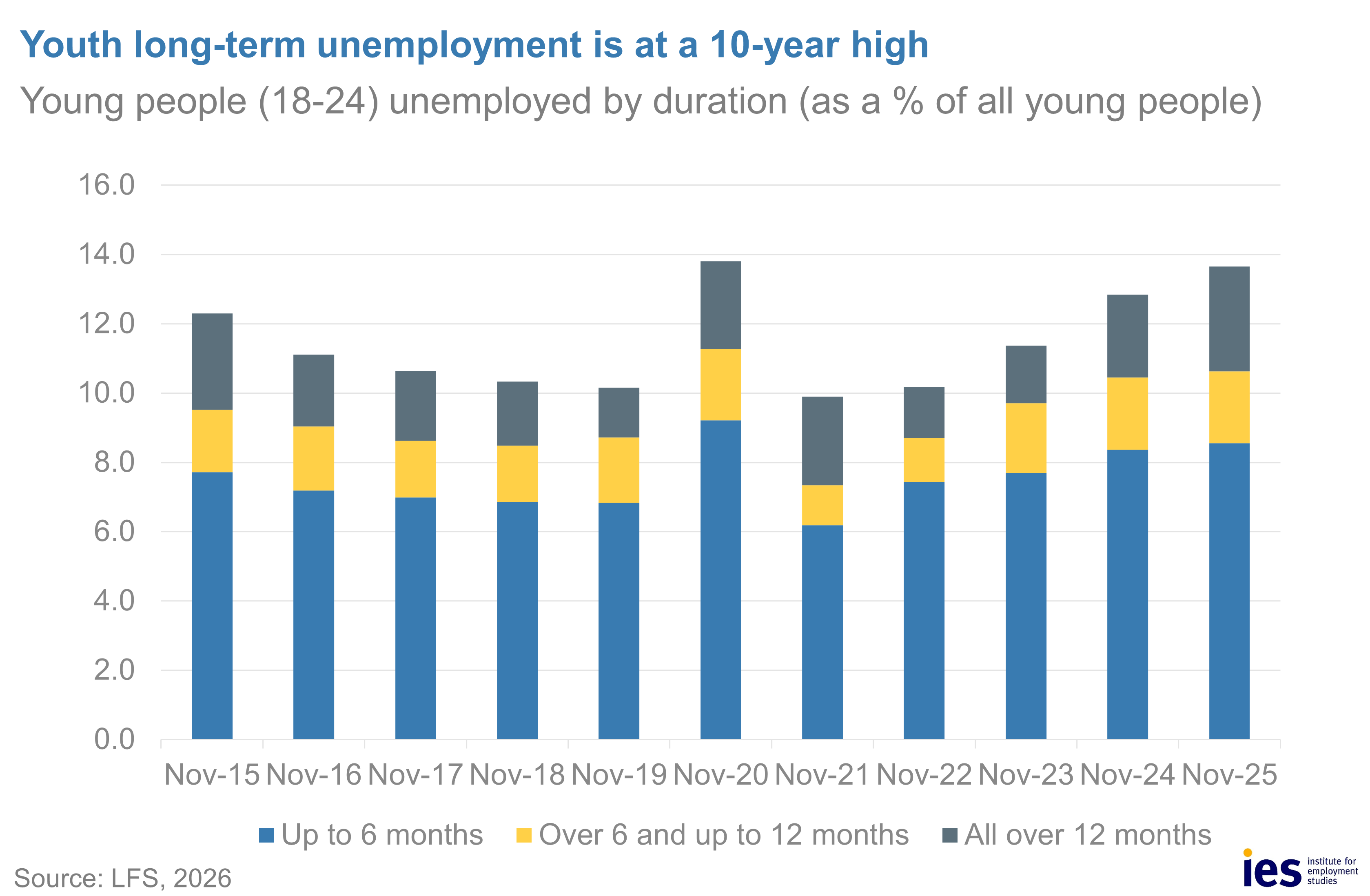

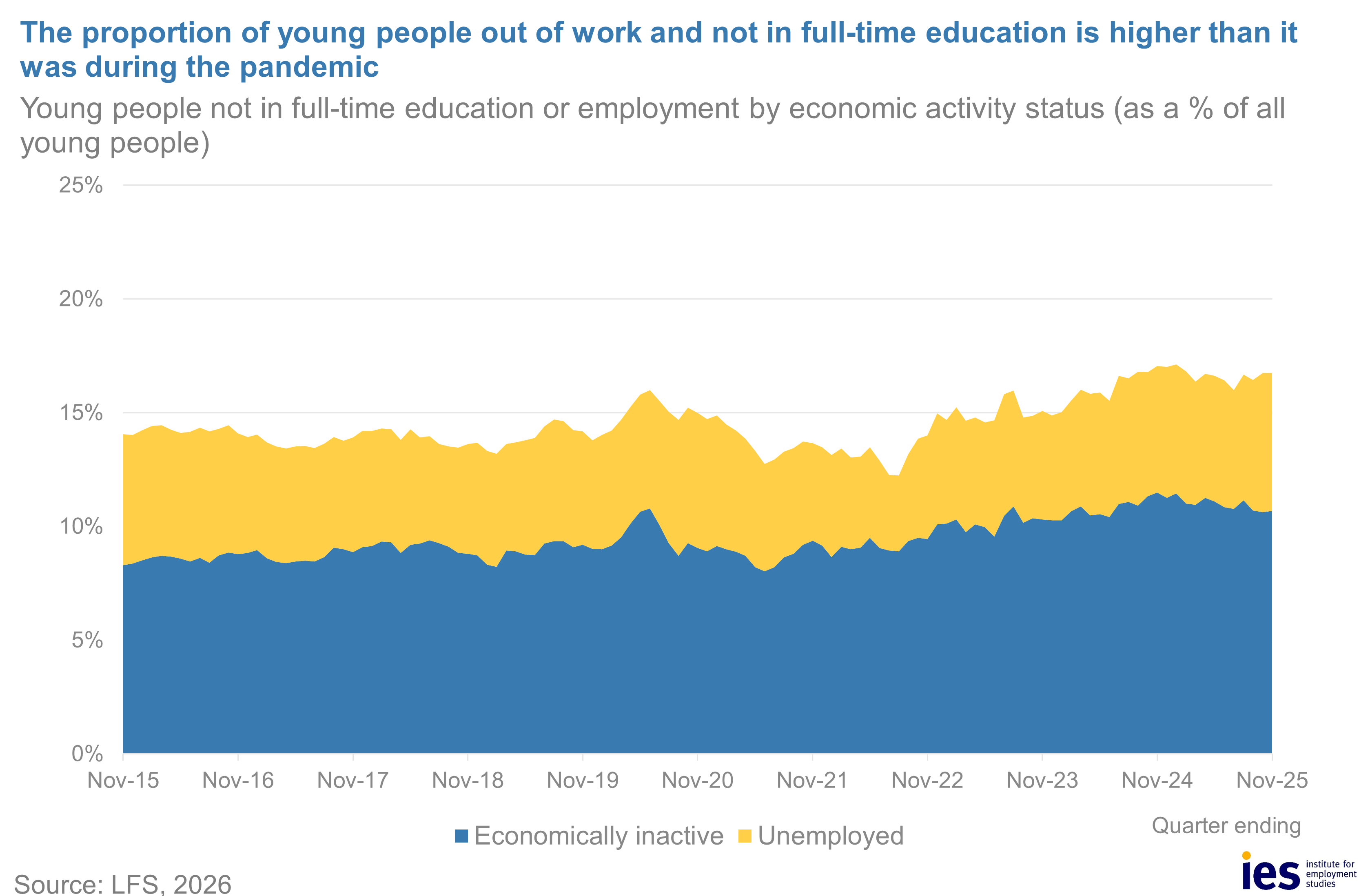

Increases in unemployment have been largely driven by young people who have been affected by the slowdown in hiring. The youth unemployment rate is the highest it has been in 10 years, including the pandemic, at 15.9%. Nearly 17% of all 16–24-year-olds are either unemployed or economically inactive and not in full-time education, which is higher than rates during the pandemic. An estimated 38% of young people, who are economically inactive and not students, are out of work and not actively looking for work due to long-term sickness – a sharp rise from 24% a decade ago and driven by increases in mental health conditions among young people.

Our latest report with Youth Futures Foundation shows that support for young people, including young people with mental health conditions, at key transition points is complex and often patchy. Long waiting lists for children’s and young people’s mental health services are driven by staff shortages and budget constraints, as spending has not kept pace with growing demand. Support is also tied to specific education providers, creating gaps at transition points and making it particularly hard for NEET young people to access help. Access often depends on disclosure, diagnosis or geography, leading to postcode lotteries and short‑term, hard‑to‑navigate support.

The government needs to urgently increase the support available for young people, particularly at key transition points, and scale up the Youth Guarantee trailblazers to help build a more joined up system. It also needs to work with employers to create more job and training opportunities for young people, and encourage hiring.

_____________________________________________________________

Any views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Institute as a whole.