Conference calls, coughs and children: Can parents really work from home?

25 Mar 2020

James Cockett, Research Economist

Dafni Papoutsaki, Research Fellow

Tony Wilson, Institute Director

The decisions over the last week both to close schools and to close large sections of the economy are having a profound and immediate effect on the labour market. While the long run impacts are uncertain, in the short term the disruption for our 11 million working parents – of whom 1.2 million are lone parents – have been particularly significant. This short briefing looks at who is in that group, the jobs that they do, and how policy still needs to respond to help meet their needs.

How many parents will be ‘key workers’?

Overall, we estimate that up to 34.7% of working age parents in employment could meet the key workers category and so be able to keep their kids in school (3.8 million). This rises to 45.8% of lone parents (0.5 million). Our estimate is somewhat higher than that of the IFS, who estimated that around a quarter of parents would still be able to keep their kids in school. The main reason for this difference is that we include local and national government workers and focus on working age individuals who are employed. Clearly though, not all eligible parents will be taking up the offer.

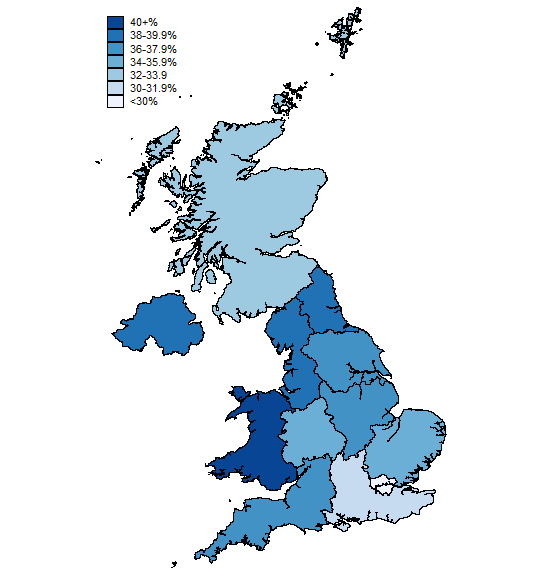

There is clear regional variation in the proportions of parents who are key workers in employment. It is lower in London (27.3%) and the South East (30.7%) and higher in Northern Ireland (38.1%) and Wales (40.9%).

Fig 1. Share of key workers in working-age population, by region

Source: Labour Force Survey

Who is left, where do they work and what might the impact be?

Our analysis shows that 7.2m parents in employment are not in one of the key workers categories. In these families, parents will have little choice but to work less – although the impacts on their labour will be different for different family circumstances, industries and occupations. Our analysis suggests that almost all industries will be affected, but to varying degrees. The four industries listed in Table 1 below each employ more than 10% of the UK workforce, but also have only a small proportion of key workers amongst their employees. Firms in these industries could therefore be disproportionately affected by the school closures.

Table 1. Sectors with largest number in employment not in key worker occupations

|

Wholesale, retail and repair of vehicles |

|

Construction |

|

Manufacturing |

|

Professional, scientific and technical activities |

The impact of this on the labour market is highly uncertain, and will depend on the job and the family. Taking these two factors in turn, clearly in some parts of the economy the impact of Covid-19 will have already had a huge effect on labour demand and so the withdrawal of parents may have little or no impact. Retail is an obvious example, and so in these circumstances the government’s Job Retention Scheme could serve to protect both parents and firms.

In other parts of the economy, the ability to work from home or to vary working hours may dampen the impact. However the ability to work from home is not as widespread as some media coverage would have us believe. The Understanding Society dataset tells us that despite a third of workers being in associate professional occupations or higher (excluding key workers), only a third (34.7%) had the ability to work from home with just 15% using this form of working regularly. Contrasting this to all other workers (key workers included), the figures are 6.5% and 2.2% respectively. Undoubtedly, the radical changes in employment practice over the last week will lead to big increases in homeworking, but it will still be a minority of workers who will be able to work in this way. Even in roles where homeworking is an option, it may not be possible to work to your full productive potential and care for kids at the same time (even if lifestyle bloggers say that you can).

Looking at family circumstances, clearly working from home with younger children will be harder than with older ones. We estimate that around 5.3 million (24.4%) of working families that are not eligible for key worker status will have children aged under 11. Working while caring will also be particularly difficult for lone parents, where we estimate that at least 700,000 that were previously working will not be eligible as key workers and will need to care for their children. This group has been largely overlooked in the discussion of the social and economic impacts of Covid-19, and needs much more consideration. By contrast in couple households, parents can either share the childcare, or choose who withdraws from work.

What needs to change?

The government’s response to this crisis has so far been significant and we have welcomed it, particularly through the Job Retention Scheme. Looking ahead though, there are several areas where support for (previously) working parents needs to be further strengthened.

Firstly, the Retention Scheme should give workers the right to be furloughed where they can’t work due to childcare responsibilities. This would help to minimise the income loss for those who cannot choose or are not able to combine work and care, or whose employers do not afford them paid time off. This will become more pressing as parents make decisions after the conclusion of the Easter holidays.

Secondly, there should be increased financial support for those who have had to leave work, been laid off or taken unpaid leave. The existing benefits system is the best way to do this, and could be achieved through further increases in Universal Credit (particularly the child elements) and in increases to contributory benefits for those not eligible for UC

Finally, lone parents will likely need particular further support the longer that restrictions on movement remain in place. One immediate step that supermarkets should take, for example, would be to prioritise lone parents for home food deliveries so that they do not need to travel to stores with their children, or at the very least to include them in the groups given early access in stores (as is happening for elderly and vulnerable people).

Note:

Characteristics of the sample: The data used is the Quarterly Labour Force Survey, October-December 2019. The `parents’ category includes parents in couples and lone parents in employment with at least one dependent child under the age of 16 years old. We exclude from the sample individuals who are either parents or children of the head of the household. The sample includes people between the ages 16 to 64. For Understanding Society the data used is from Wave 8 (2016-18) and includes all working age adults.

Any views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Institute as a whole.