Making apprenticeships more inclusive

1 Feb 2014

Becci Newton, Principal Research Fellow

Although there has been a policy focus on addressing under-representation in apprenticeships, particularly by gender,[1] over many years, achieving progress on the inclusion of women and ethnic minorities has proved challenging. For example, gender segregation cuts across ethnic and cultural identifies, and ethnicity can compound the impact of occupational gender segregation. We look at the issues, drawing on recent IES research.

Although there has been a policy focus on addressing under-representation in apprenticeships, particularly by gender,[1] over many years, achieving progress on the inclusion of women and ethnic minorities has proved challenging. For example, gender segregation cuts across ethnic and cultural identifies, and ethnicity can compound the impact of occupational gender segregation. We look at the issues, drawing on recent IES research.

Apprenticeships are going through a process of radical change following the recommendations of the Richard Review.[2] It is therefore timely to look again at equality and diversity in the programme, drawing on recent IES research. While women currently represent more than 50 per cent of apprentices, they are often training in sectors that have low pay or offer few opportunities for career progression. The conversion of existing employees to apprenticeship training is also far more prevalent among women than men. Accordingly female apprentices are older than their male counterparts: 47 per cent of female apprentices are aged 25 and over compared to 36 per cent of male apprentices. In contrast, only 25 per cent of female apprentices are aged 16-18 years whereas 35 per cent of male apprentices are in this age band. This all suggests that apprenticeships struggle to attract younger women. Among ethnic minorities, the overall low rate of participation is the concern, although participation also varies considerably between different ethnic groups and, for some ethnic minority communities, it is far lower than would be expected based on population data.

TUC unionlearn, with funding from the National Apprenticeship Service, commissioned IES to lead research into under-representation by gender and among ethnic minority groups in apprenticeships. As part of this, we explored the decisions made by young people about their careers and about pursuing apprenticeships as a means to achieve their career goals. Employer practices were examined to determine if any strategies or practices had the effect of excluding women or ethnic minority groups. We canvassed the opinions and practices of providers, schools and other stakeholders, including those who support apprentices in the workplace.

The research demonstrated that gender segregation within apprenticeships cuts across ethnic and cultural identities and that ethnicity compounds the impact of occupational gender segregation. This may be attributed, in part, to cultural and religious restrictions on the nature of work that women from some ethnic minority groups may undertake. However, women predominate in Advanced and Higher Apprenticeships, irrespective of ethnicity and there is a developing view that Higher Apprenticeships are overcoming the diversity challenges seen within the lower levels of training and as such, may provide a means to tackle the esteem and parity of Apprenticeships in relation to higher education. This suggests that gender equality may improve as part of the drive to increase the quality of apprenticeships.

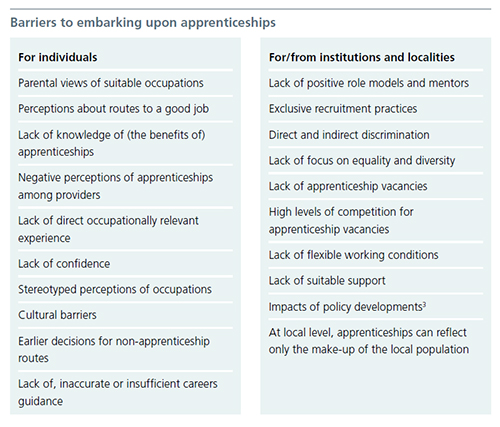

Barriers to embarking upon apprenticeships

We found a wealth of evidence and opinion about the barriers to apprenticeships for both groups and the factors that lead to occupational segregation. However, it was also clear that there has been little change over time, suggesting there is a gap in action rather than in knowledge. The main barriers are set out in the table below.

Key recommendations

The research culminated in recommendations to increase the esteem in which apprenticeships are held, to raise awareness of them more broadly, and to increase coverage of the opportunities afforded by apprenticeships in careers guidance in schools. While these sound simple to put into action, the new commissioning arrangements for careers guidance in schools may result in inconsistencies and differing emphases on training rather than study between schools. Moreover, teachers and parents are important influencers of young people and they may have out-of-date notions of apprenticeships and careers that need to be overcome if underrepresentation is to be tackled.

Specific recommendations were also made for the two key groups. These included, for ethnic minorities:

- More detailed exploration of prior qualifications and employability of those registered on the Apprenticeships Vacancies system, since there are far more ethnic minority applicants are apprentices.

- A detailed examination of employer recruitment strategies to understand whether there is evidence of (unwitting) discrimination. We also saw a role for employers already engaged on this agenda to promote the business case for diversity to other employers.

- Education and training providers should seek to present more diverse shortlists of candidates to employers and work more closely with employers on recruitment, by sitting on recruitment panels to ensure fair and equal recruitment practices are used.

- To compete more effectively for apprenticeships, young people from some ethnic minority backgrounds need to attain better Key Stage 4{4] qualifications. To do this requires ambitions to be raised and may entail support starting in much earlier phases of learning.

- The provision of role models to act as a source of inspiration and support to young people from diverse backgrounds.

- Emphasis on the role of apprenticeships as a route to professions as well as trades. Our research showed that for some ethnic minority groups, particularly those from migrant backgrounds, the message about quality is particularly important.

- Religious considerations relate to but are different from general messages about ethnic under-representation. Some religious groups require minor adaptations to working conditions to allow, for example, time and space for prayer.

The actions necessary to increase representation of women in apprenticeships are well established. We reiterated them in our report, with indications of organisations that could provide a lead on addressing and, more crucially, embedding them in practice. To increase gender equality in apprenticeships, what is needed includes:

- Better-quality, more in-depth and challenging careers guidance at an earlier age that, crucially, addresses occupational stereotypes. This should include information about how career choices affect future pay and progression.

- Knowing about discrimination or division in an employment sector can deter people from considering that work. Therefore, more must be done to convince young women that the door really is open to them.

- Role models can be a powerful influence on young women. Our research found that young women who enter nontraditional apprenticeships did so because they had family members working in the sector. Widening who influences young people beyond the immediate family is of critical importance if there is to be a genuine attempt to widen career horizons.

- The lack of funding to support the costs of childcare while undertaking an apprenticeship may deter young parents from the programme.

Next steps

Unionlearn is now seeking to respond to the recommendations and recently held a launch event to create momentum behind the agenda. It is also giving evidence at a joint meeting of the Equalities Advisory Group/ Ethnic Minority Employment Stakeholder Group. Unionlearn director, Tom Wilson said, ‘The research provides compelling reading. Everyone involved in apprenticeships, from policymakers to practitioners, should read it and consider how both findings and recommendations can be acted upon to ensure an apprenticeship programme that works for all. Unionlearn looks forward to working with Government, the National Apprenticeship Service, employers, unions and other stakeholders to ensure that this happens’.

What is certain is that it will take concerted and collaborative effort to address the under-representation we currently see in the apprenticeship programme since it involves addressing the drivers of occupational segregation more generally. It will also require continued monitoring and ongoing interest among policymakers.

Footnotes [back]

[1] For example, DCSF, DIUS (2008). World-class Apprenticeships: Unlocking talent, building skills for all; the EOC inquiry into gender equality and modern Apprenticeships (see below).

[2] The Richard Review of Apprenticeships, published in November 2012, looked at how apprenticeships in England can meet the needs of the changing economy: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/ the-richard-review-of-apprenticeships

[3] For example, see commentary about the withdrawal of Train to Gain funding and the rising trend of ‘conversion’ Apprenticeships.

[4] Key Stage 4 is the legal term for the two years of school education which incorporate GCSE (General Certificate of Secondary Education) exams in the UK, during which pupils are aged between 14 and 16.