Rethinking the productivity–pay relationship: implications for innovation policy

7 Jan 2026

Nick Litsardopoulos, Research Economist (Fellow)

This blog was originally published in December 2025 on the website of Adzuna, one of the largest online job search engines in the UK.

The 2025 Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel was recently awarded to Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion, and Peter Howitt “for having explained innovation–driven economic growth”. Their work continues a long tradition, beginning with Schumpeter’s “gale of creative destruction”, recognising technological innovation as a transformative force that raises demand for new products, services, and skills while rendering others obsolete. Despite short–term disruptions, few dispute that technological progress has improved long–run human welfare.

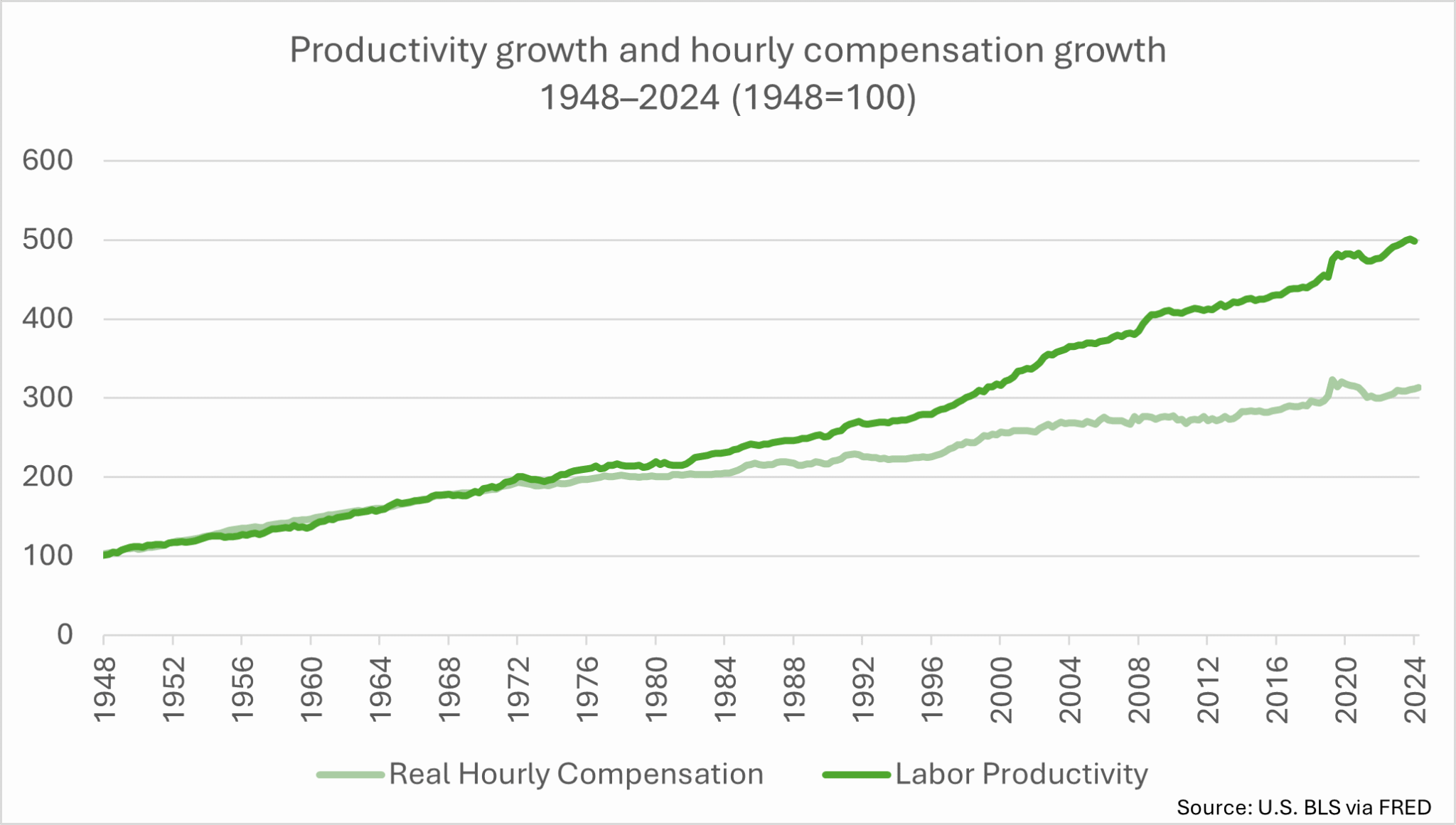

Yet, prominent thinkers such as Carl Benedikt Frey and Martin Ford have voiced concerns about how the benefits of technological progress are shared. Central to these concerns is a widely circulated chart showing that, since the mid 1970s, measured labour productivity in the United States has risen substantially, while real hourly compensation for typical workers has stagnated. The version of this chart reproduced below illustrates this familiar divergence.

Figure 1. Productivity growth and hourly compensation growth, 1948–2024 (Source: U.S. BLS via FRED)

This “productivity–pay gap” has become a touchstone in debates on automation, inequality, and labour policy.

Technological progress should, in theory, accelerate productivity growth and thereby raise incomes. Indeed, productivity analyses suggest that without productivity growth, workers’ pay would have been even lower. However, a divergence has appeared, that is, the average compensation has continued to track productivity fairly closely, while nonsupervisory wages have lagged significantly. This decoupling has shaped decades of policy debates premised on the expectation that productivity and pay should rise together.

Do we really measure what we think we’re measuring?

Productivity appears straightforward, that is, output divided by input, but becomes difficult to interpret across complex economies. In a factory producing identical widgets, output per hour worked is easy to measure. But modern economies produce thousands of heterogeneous goods and services. How do we compare the output of a care worker with that of a software engineer?

Economists solve this problem by using prices to convert all goods and services into monetary value. Yet this creates a conceptual complication: when output is measured in monetary terms, “productivity” becomes difficult to distinguish from income. Labour productivity, measured as value added per worker, is essentially total income (minus intermediate inputs) divided by the number of workers. Comparing productivity and wages, therefore, becomes close to comparing two different forms of income rather than assessing a relationship between physical output and compensation.

The correlations we observe tell us something important about income distribution, but less about whether workers are becoming more efficient or “creating more” in a physical sense.

Rethinking the productivity-pay gap

The familiar chart suggests that workers are producing more, but not being compensated accordingly. Yet once measurement issues are acknowledged, the gap reflects a different underlying dynamic.

Two forces drive the divergence:

- A declining share of national income going to labour relative to capital, and

- Rising inequality within labour income, whereby top earners capture a disproportionate share of total wage growth.

While top earners experienced wage increases of around 160% over the period, typical workers saw little real growth. The divergence is real and economically significant, but it is fundamentally a distributional phenomenon, which is less a story of workers being underpaid relative to output and more one of changing income shares.

This distinction matters for policy. If the issue were simply that workers are producing more, but receiving less, then policymakers might focus on collective bargaining or minimum wage laws. However, if the central problem is the distribution of income between labour and capital, or within the labour force itself, then policies must also address capital concentration, market power, and institutional frameworks shaping how economic gains are shared.

What is actually happening to productivity?

When we examine productivity in physical or energy–based terms, that is, how effectively we transform inputs into useful outputs, growth has largely stagnated since the 1970s, contrasting sharply with monetary measures showing steady increases. Industry–level analysis reveals some exceptions, but overall, much of the apparent productivity growth captured by traditional metrics reflects:

- changes in prices

- shifts in industrial composition

- inequality effects embedded in averages

- changes in accounting conventions

Meanwhile, transformative innovations in information and communication technologies have created tremendous value, but often in ways that escape conventional productivity measures.

Implications for innovation policy

The UK’s Industrial Strategy seeks to tackle historically low business investment, weak productivity growth, and limited market dynamism. However, if productivity measures conflate income and output, policymakers must exercise caution when using them to guide innovation policy. Alternative measures, such as, Total Factor Productivity (TFP), Gross Value Added (GVA), inclusive GVA, Beyond GDP metrics, and the Human Development Index (HDI), offer broader perspectives on wellbeing and economic change.

From an innovation–policy perspective, several insights emerge:

- Different types of innovation have different productivity signatures.

Some innovations reduce energy use or create new non–market forms of value. These may not appear as productivity gains even as they reshape labour markets. - Productivity metrics should be used with humility.

Paul Krugman famously wrote that “productivity isn’t everything, but in the long run it is almost everything.” Nevertheless, if our metrics are imprecise proxies, they must be interpreted cautiously. - Distribution is as important as growth.

Innovation can boost national output, but whether its benefits are broadly shared depends on policy choices, institutional design, and bargaining structures.

Policy recommendations

In light of these dynamics, several policy implications follow:

- Clarify what “productivity” means in specific policy contexts.

Policymakers should indicate whether they target higher physical output, value added, technological capability, or energy efficiency. - Evaluate innovation not only by productivity metrics but by distributional outcomes.

Who benefits, and who does not, should be central to assessment. - Use income distribution measures directly when assessing fairness of compensation.

Avoid relying solely on productivity–wage comparisons. - Be explicit about which productivity measure is being used and what it captures.

The choice of metric can significantly influence policy conclusions.

Innovation remains essential for long term prosperity, but its relationship to wages and productivity is more complex than conventional charts suggest. Policymakers should understand which measure is being used and what it actually captures when productivity statistics inform policy debates. Having a clearer understanding of distributional dynamics are essential to design innovation policies that can support both growth and shared prosperity.

As a UN Development Policy and Analysis Division concluded: “If technology leads to less equal income distribution, policies are called to redistribute income.”

Any views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Institute as a whole.