The unintended consequences of good intentions: how recent UK employment policy changes are reshaping the jobs market

18 Jun 2025

Nick Litsardopoulos, Research Economist (Fellow)

This blog was originally published in June 2025 on the website of Adzuna, one of the largest online job search engines in the UK.

When good intentions meet market reality

The recent changes in the UK National Insurance Contributions (NIC) and the National Minimum Wage have shifted the dynamics in the jobs market and created a new environment that employers and employees need to navigate. The changes represent well-intentioned efforts to boost worker incomes and government revenues. However, these policies are creating ripple effects throughout the employment landscape that extend far beyond their original objectives. The dual impact of higher employment costs is fundamentally altering how employers approach hiring decisions, with consequences that are reshaping the entire jobs market in ways that policymakers may not have fully anticipated. Above all, these policy changes are taking place during a period when ONS observes that job vacancies have been declining for the 34th consecutive quarter, with quarterly falls seen in 13 out of the 18 industry sectors.

The numbers tell a stark story about the financial pressure these changes have placed on employers. From April 2025, employers face a 1.2 percentage point increase in National Insurance contributions, pushing the rate to 15%. This translates to an additional £900 per year for each employee earning median wages. When combined with minimum wage increases, the cost of hiring a full-time worker on the National Living Wage has jumped by 7.1% in real terms – more than double the cost increase for average earners. However, the new government measures also increased the maximum Employment Allowance from £5,000 to £10,500. For businesses already operating on tight margins, particularly small and medium enterprises that form the backbone of the UK economy, these changes are a significant challenge that may require careful accounting. Regardless, the combined impact on lower-wage workers means that the very people these policies aimed to help may find themselves facing higher barriers to employment as employers recalculate the economics of hiring. The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) estimated the increase in employer NICs will reduce the level of potential output by 0.1% at the forecast horizon.

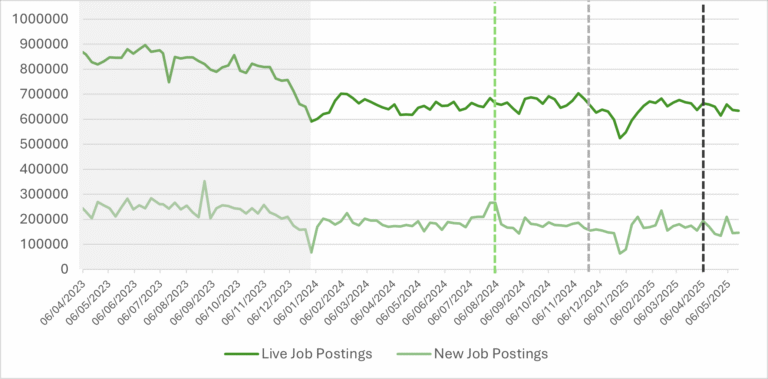

The employment market’s response has been swift and measurable. The ONS May Labour market overview shows that overall job vacancies declined to 761,000 between February and April 2025, marking a 15% drop compared to the same period the previous year. This represents not just a pause in hiring growth, but an active contraction in job opportunities. Using data from Adzuna’s intelligence portal we can see the available live job postings and the new job postings. We plot the job postings data over the period 2016-2025 and note the dates for the Minimum Wage announcement in October 2024 (light green dashed line), NIC/Employer Allowance announcement in November 2024 (light grey dashed line), and the implementation in April 2025 (dark grey dashed line).

Taking a longer view reveals that the decline in job postings has been an ongoing problem. Additionally, we see that the market reaction to the October 2024 government announcement for the Minimum Wage increase and the November 2024 government announcement for the NIC and Employer Allowance changes was stronger than the reaction to the implementation of the changes in April 2025. What is more is that we can see that in the intermediate period there was an increase in new job postings, highlighting the volatile jobs market environment, and the increased nervousness of employers. While the data indicate that it is true that the market reacted negatively to the NIC changes, the new job postings data reveals that the market reaction to the October 2024 Minimum Wage announcement (light green dashed line) was more severe than the NIC announcement, and it seems to have reversed a previously increasing new job posting trend.

Taking a longer view reveals that the decline in job postings has been an ongoing problem. Additionally, we see that the market reaction to the October 2024 government announcement for the Minimum Wage increase and the November 2024 government announcement for the NIC and Employer Allowance changes was stronger than the reaction to the implementation of the changes in April 2025. What is more is that we can see that in the intermediate period there was an increase in new job postings, highlighting the volatile jobs market environment, and the increased nervousness of employers. While the data indicate that it is true that the market reacted negatively to the NIC changes, the new job postings data reveals that the market reaction to the October 2024 Minimum Wage announcement (light green dashed line) was more severe than the NIC announcement, and it seems to have reversed a previously increasing new job posting trend.

Unintended consequences for economic participation

This brings us to another big problem that is related to the dynamism of the British labour market. Perhaps an even more concerning development is how these employment cost increases may be contributing to higher rates of economic inactivity. As job opportunities become scarcer and entry requirements higher, some individuals may find themselves effectively priced out of the labour market. The combination of fewer available positions and elevated skill requirements creates a barrier that can discourage job seeking altogether. This is particularly problematic for regions already struggling with high inactivity rates (e.g. the North East), where local employers may lack the resources to absorb higher employment costs. The result is a perverse outcome where policies designed to improve workers’ financial situations may inadvertently reduce the number of people able to participate in the workforce. Additionally, wage compression effects – where minimum wage increases squeeze the differential between entry-level and slightly higher-skilled positions – can reduce incentives for career progression and skill development, potentially undermining long-term economic mobility.

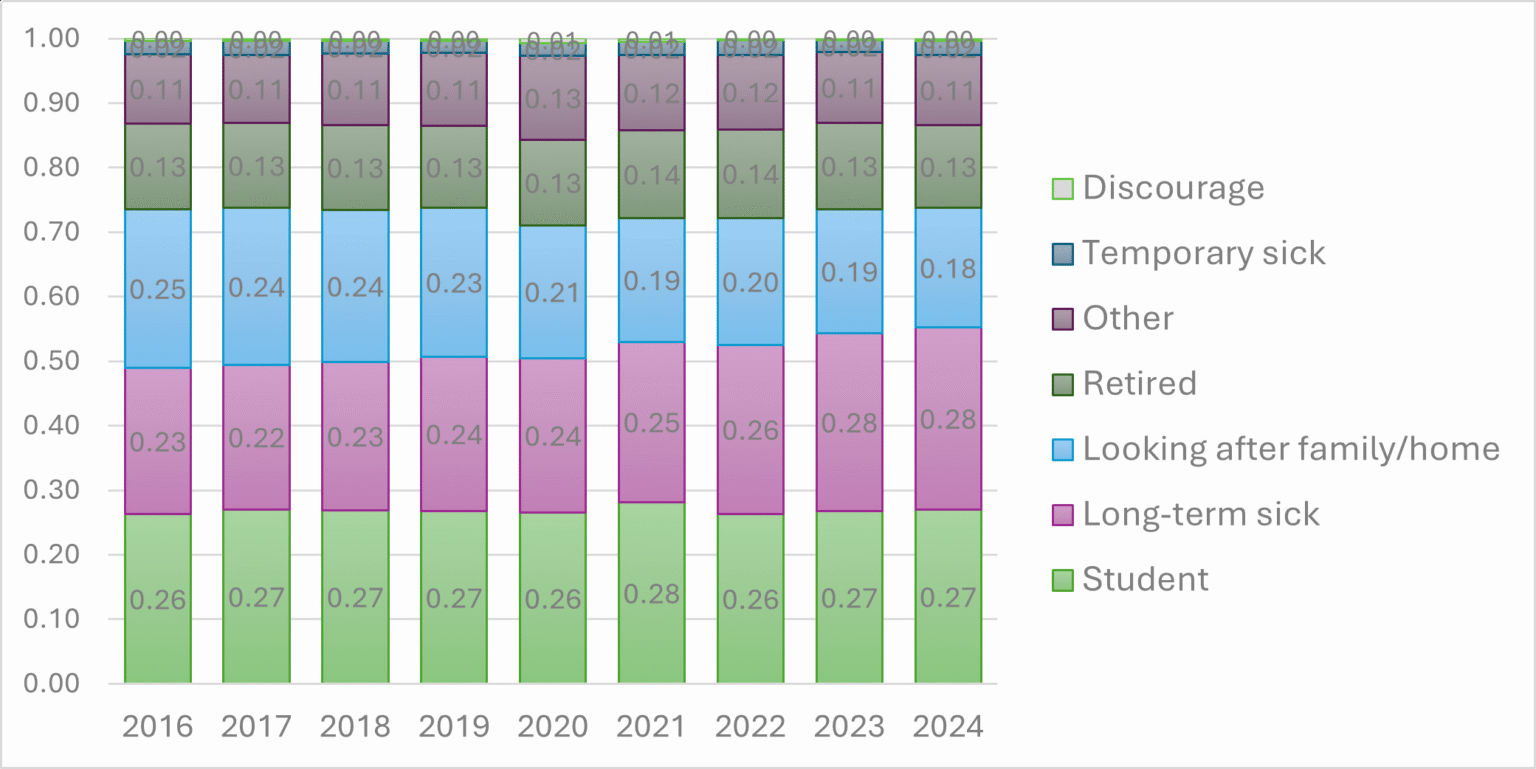

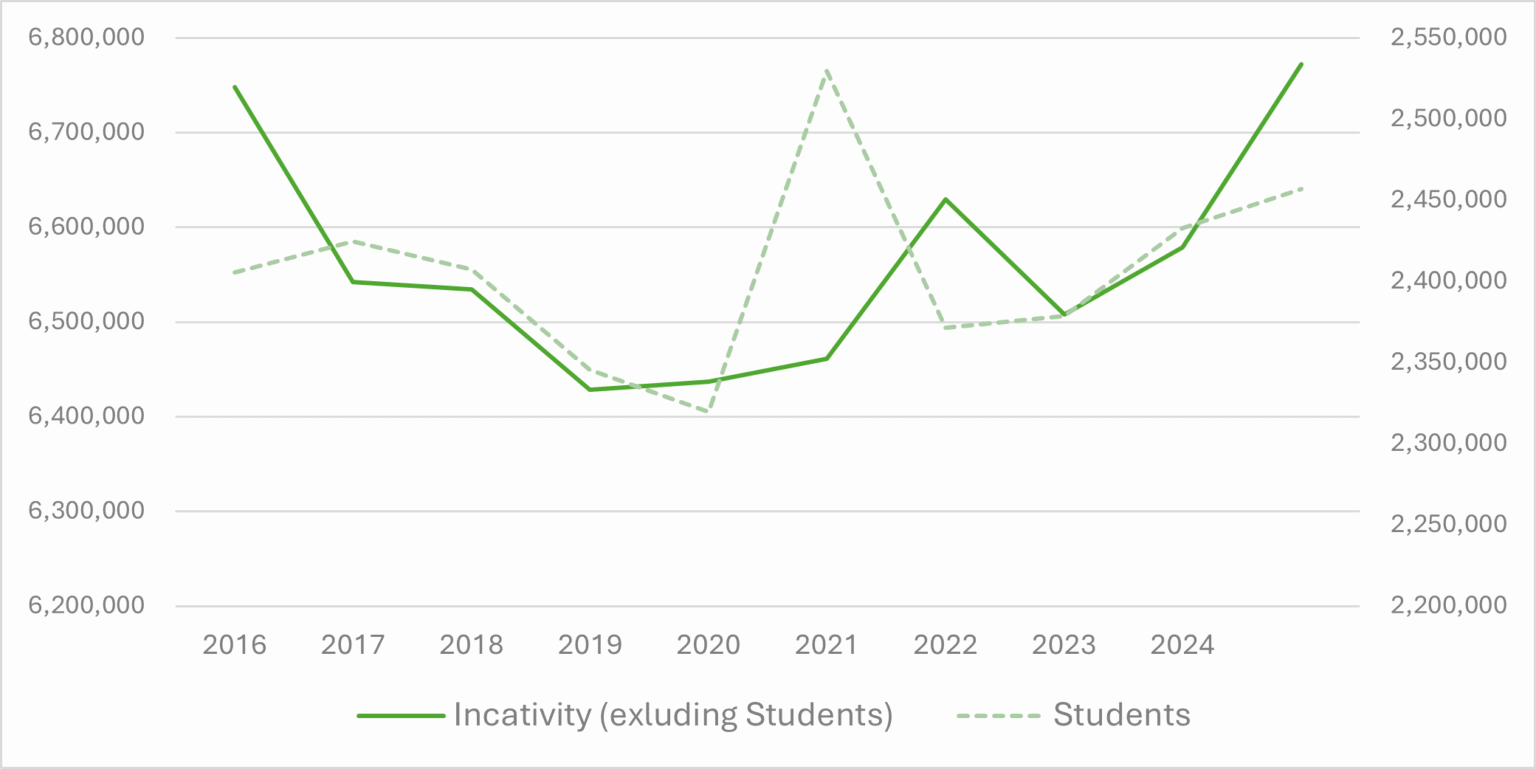

Adzuna’s Intelligence Portal offers economic indicators about the reasons for inactivity collected from ONS data. Two reasons that stand out are the “Looking after family/home” which has decreased over the years, and the “Long-term sick” which has increased over the same period. The total number of economically inactive stands at about 9 million people, more or less at the 2016 levels, after a period of decreasing inactivity in the pre-pandemic years that saw inactivity fall to just above 8.7 million people in 2020, before rising again.

When we exclude those who cited education as the reason for their inactivity (i.e. student), we see the overall pattern of falling then rising inactivity but with some nuances. For example, inactivity due to being a student spiked in 2021, whereas inactivity (excluding students) had a spike, albeit a smaller one, a year later in 2022. These could be some of the students who simply completed their first year studies, but continued to be inactive afterwards. Nevertheless, the number of inactive people is higher today than it was in 2016, with the increase not showing any indication of slowing down. This indicates that while it is true that a substantial share of those inactive are students, this alone does not change the fact that inactivity has been increasing for reasons other than more people studying or staying in education longer.

The challenge facing policymakers is reconciling the undeniable benefits these changes bring to employed workers – with over 3 million eligible for pay rises of up to £1,400 annually – against the broader employment effects that may be limiting opportunities for others. The early evidence suggests that while those in employment are benefiting from higher wages, the pathway into employment is becoming narrower and more challenging to navigate. This creates a two-tier effect where the employed see improved conditions while the unemployed or inactive face increased barriers to joining them. The solution likely requires a more nuanced approach that considers not just the direct effects of policy changes on those already in work, but also their impact on employment creation and access. Future policy adjustments may need to include targeted support for small businesses, incentives for hiring entry-level workers, or complementary measures that help bridge the gap between policy intentions and market realities. The goal should be ensuring that efforts to improve working conditions do not inadvertently close the door on those seeking to enter the workforce in the first place.

The challenge facing policymakers is reconciling the undeniable benefits these changes bring to employed workers – with over 3 million eligible for pay rises of up to £1,400 annually – against the broader employment effects that may be limiting opportunities for others. The early evidence suggests that while those in employment are benefiting from higher wages, the pathway into employment is becoming narrower and more challenging to navigate. This creates a two-tier effect where the employed see improved conditions while the unemployed or inactive face increased barriers to joining them. The solution likely requires a more nuanced approach that considers not just the direct effects of policy changes on those already in work, but also their impact on employment creation and access. Future policy adjustments may need to include targeted support for small businesses, incentives for hiring entry-level workers, or complementary measures that help bridge the gap between policy intentions and market realities. The goal should be ensuring that efforts to improve working conditions do not inadvertently close the door on those seeking to enter the workforce in the first place.

Any views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Institute as a whole.