Behaviours that work in helping people find work: how we can use Behavioural Insights to improve employment outcomes

Behavioural Insights, an approach that aims to determine what drives behaviour in order to change behaviour, have seen increasing use in employment programmes. Miguel Subosa highlights findings from recent ReAct research regarding behaviourally informed employment programmes and lays out recommendations to help improve employment support services.

Most of us have seen Behavioural Insights in action, perhaps without even being aware of it. When shopping for groceries, have you ever paid attention to the green, amber, and red labels on the package, indicating how much of each nutrient a product contains? If you have, then you are no stranger to Behavioural Insights.

Behavioural Insights have seen increasing use in public policy over the past decade, and employment programmes are no exception. A recent IES report, published through the ReAct Partnership, explores existing research regarding behaviourally informed employment programmes. This blog highlights some headline findings. Drawing on these findings, we lay out recommendations to help improve employment support services. Before that, though, what constitutes ‘Behavioural Insights’?

A nudge towards our best behaviour

Put simply, Behavioural Insights is a policy approach that aims to determine what drives behaviour in order to change behaviour. An important concept in Behavioural Insights is nudge theory. Nudging pertains to the implementation of small changes in the environment to induce change in individuals’ behaviour, without directly limiting their choices. Remember the traffic light labels? Those are a prime example of nudging – and a very effective one at that. Besides the evidence documenting their effectiveness, nudges have become a popular policy instrument also because they are cheap to implement.

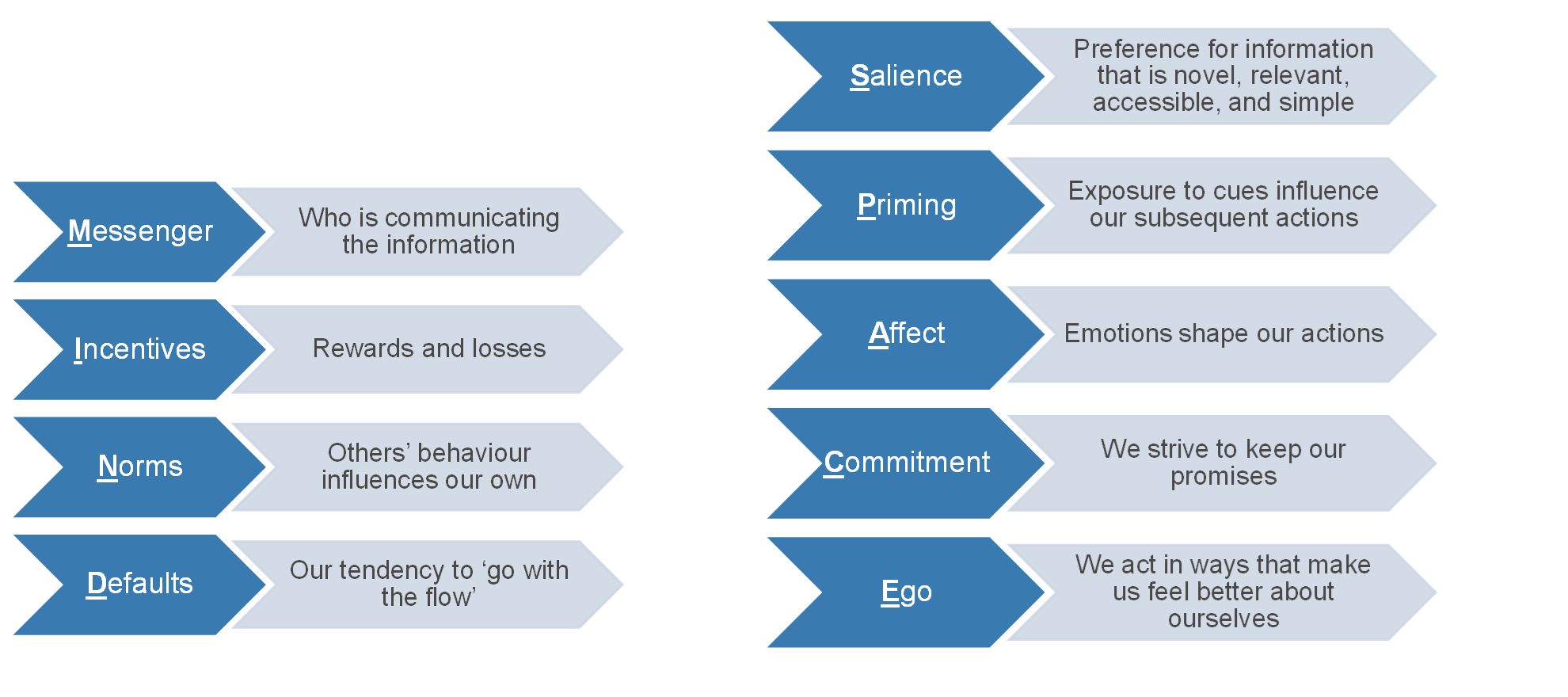

This begs the next question: which motivational factors should nudges focus on to be most effective? Human motivation is complex and is influenced by a wide array of factors. The MINDSPACE framework lays out some of the most important ones.

It must be noted, however, that MINDSPACE should not be treated like a checklist. Nudge interventions work best when they: (a) target one or two specific behaviours and (b) are designed based on the factors identified by the evidence as being most influential on the target behaviour.

Informed by nudge theory, we examined the research evidence pertaining to behaviourally informed employment support policies and programmes, extracting practicable insights for support providers.

Nudging people closer to employment

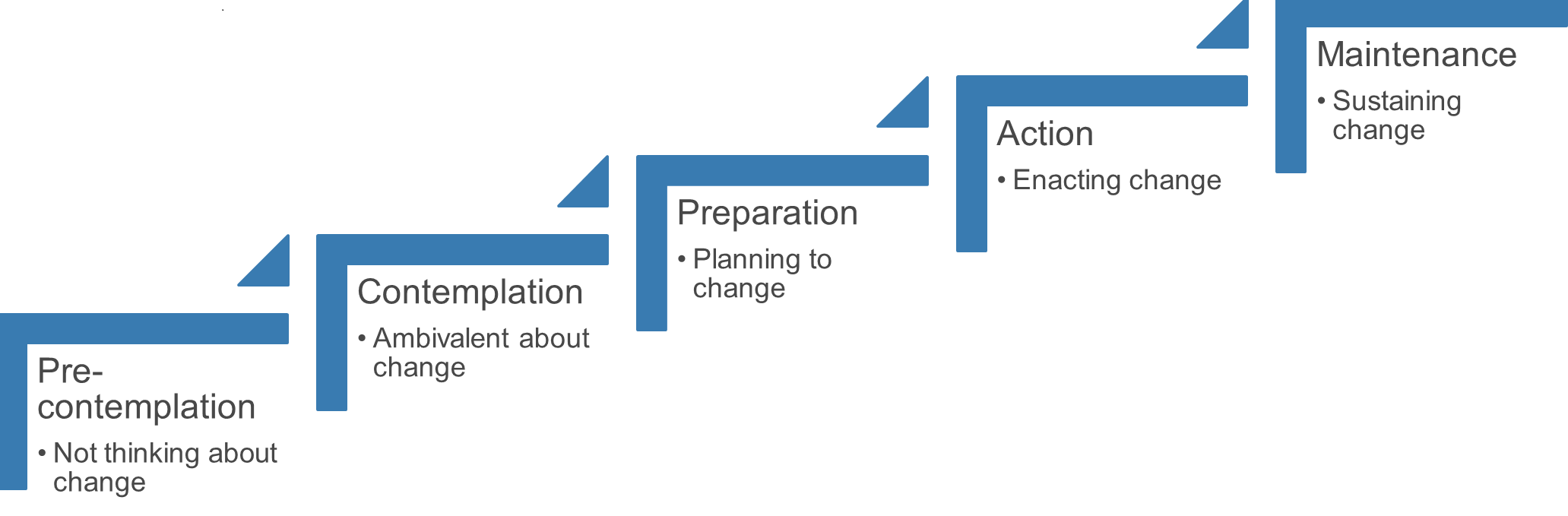

Folk wisdom tells us that change does not happen overnight, and research confirms this. Change is a process, and experts have come up with different frameworks to capture this. One framework that has been found to produce desirable results amongst jobseekers is a five-step process, illustrated below.

At any given time, a jobseeker would be at a certain step on this change process. One study we included in our review, which looked at how normative feedback influenced behaviour, found that individuals were most receptive, and thus more likely to change their behaviour, if the feedback they received was tailored to where they were on this process. For instance, a jobseeker at pre-contemplation stage might be prompted to think about changing by presenting them with information comparing them to peers who have successfully begun their job search. When a jobseeker is at action stage, an employment adviser might provide information on the jobseeker’s progress to sustain their motivation. The effectiveness of this approach attests to the importance of providing support that is tailored to jobseekers’ skills and motivations.

An experiment conducted with young adult jobseekers in Austria confirms the effectiveness of individualised support. The said experiment found that information worked best when it was preceded by self-reflection. The findings of this experiment point to ways in which employment advisers might want to structure appointments with jobseekers to improve outcomes. For instance, appointments with jobseekers could be started with a conversation about the jobseeker’s skills, motivations, and objectives. This approach may help jobseekers be more receptive to subsequent employment advice. Such an approach could even be bolstered by enlisting the commitment of jobseekers.

Studies affirm the effectiveness of commitment declarations, with researchers finding a positive association between written commitments and desirable employment outcomes, such as training attendance and off-flow from benefits. The use of such commitment devices are becoming increasingly popular amongst employment support providers, and for good reason.

The studies we examined also showed that these commitment devices worked well in conjunction with the right incentives, especially when those incentives are also rightly framed. For instance, the same research on training attendance mentioned previously also found that jobseekers were more likely to attend the training they had committed to when they were reimbursed for the costs, compared to when they were given a reward for attending. In sum, incentives of the same monetary value had significantly different effects. Therefore, employment support providers should consider not only the kinds of incentives they offer but also the way those incentives are framed and administered.

Indeed, our literature review confirmed the potential of nudge-based employment support interventions to improve job-related outcomes. However, nudges are not a panacea towards improving employment outcomes.

Support provider, beware

Like all of us, jobseekers are affected by broader circumstances that no kind of nudge can address. Yes, small nudges can set the stage for positive job-related outcomes, but effective support also recognises systemic barriers that prevent sustainable employment.

For instance, one cannot expect a jobseeker with heavy loads of childcare to prioritise employment without any kind of structural support to alleviate some of that load. Providing that structural support falls in the hands of employers and policymakers. There are various ways to address this, such as making day care facilities more financially accessible or allowing more flexible working arrangements for carers.

Similarly, we cannot claim to advocate for sustainable employment without acknowledging the intensifying precarity of modern work, which has only been aggravated in the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic. Two-thirds of the employment growth following the 2008 financial crisis is from precarious work, and deteriorating work conditions are most felt by those already earning lower incomes to begin with. How then can we expect jobseekers to find sustainable employment if the opportunities for sustainable employment are ever narrower?

These are not questions of small-scale nudging but of larger policy changes. Sometimes a nudge might work, but building a larger system that favours sustainable employment requires a far stronger response.

To read the ReAct evidence review of Behavioural Insights in employment support services please click here

Any views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Institute as a whole.