Employer investment in training in England

6 Apr 2023

Becci Newton, Director, Public Policy Research

This analysis was originally published in Campaign for Learning's 'Driving-up employer investment in training - pressing the right buttons'. The Campaign for Learning’s report includes analysis and recommendations on how to boost the demand for skills and employer investment in training from 21 leading organisations and experts.

_____________________________

Over decades, a problematic trend in the UK has emerged – employers are failing to invest in training the workforce, despite technological change and the need to address climate change.

Employer Investment has flat lined since 2015

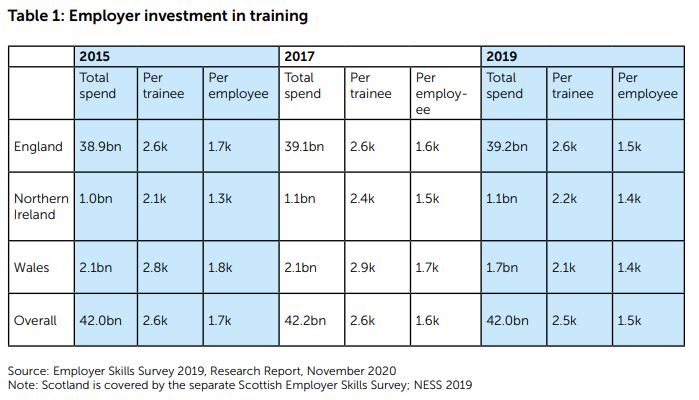

Data from the Employer Skills Survey shows that overall investment in training by employers in England, Northern Ireland and Wales was flat in real terms between 2015 and 2019 (see Table 1). That was pre-pandemic so it is likely that worse news is to follow in the next survey.

In England, investment in training has increased very modestly from £38.9bn in the 2015 survey to £39.2bn in the 2019 survey. But while investment per trainee also remained remarkably stable between 2015 and 2019 at £2.6K, the spend on training per employee in England declined by £200 in real terms. In addition, the average number of training days per trainee in England fell from 6.8 in 2015 to 6.0 in 2019.

Perhaps a factor that helps explains these trends in England – a flatlining in spend per trainee, a modest declining trend in spend per employee and a fall in the number of training days per trainee - concerns the form of training that are recorded by ESS. Analysis by IES finds that “training is often geared towards induction and health and safety”.

Training Spend Per Employee by Employers has Plummeted

Over a longer time scale, a recent report by the Learning & Work Institute estimates that training spend per employee “plummeted by 28 per cent” between 2005 and 2019. The authors note that this level of investment lags substantially behind employers in Europe who invest twice as much per worker than in the UK.

Declining Participation in Work-Related Training

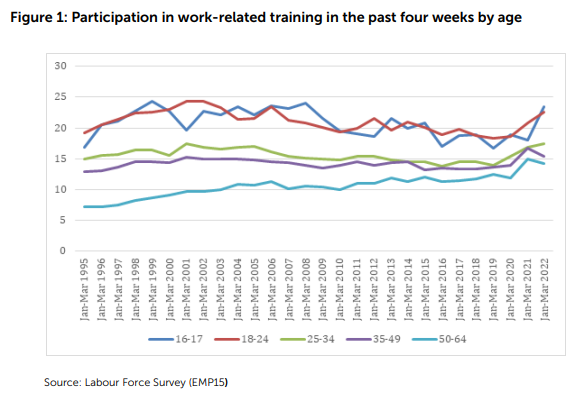

Another study by CIPD tracks a significant decline in participation in work-related training drawing on the Labour Force Survey. It shows that the rate of training in the first quarter of 2018 was about the same as it was in the same period in 1996 at around 14 per cent of all employees aged 16 to 64. The latest LFS data shows this figure increased to 17 per cent in the same quarter of 2021 and was stable at 17 per cent in 2022 (see Figure 1). However, before congratulating employers on changing tack, it is worth considering that in this timeseries, since 1995, this rate has not been exceeded in any quarter-year.

Figure 1 also shows the rate of this training by age between 1995 and 2022 based on first-quarter data. While younger employees remain the most likely to receive training, the gap between them and middle-aged and older workers has narrowed substantially over time.

It is a positive sign that older employers are being invested in, albeit they experience the basic level of training necessary to work. However, the downturn for those aged between 35 and 49 should be a cause for concern, given the policy drive that this group should work for to a minimum of 67 years of age.

A more positive view would be presented by a narrowing of the gaps but with each age group seeing an increasing trend for occupational training, which is far from the case. Younger workers are seeing a return to the levels of training they saw before the great recession but there appears a risk that training among middle-aged and older workers is stagnating.

A Change is Needed

It is unarguable that change is needed. In parallel to encouraging and supporting people to enter the labour market - which requires making work more accessible, there is a need to consider the role for government investment to drive employer investment in rates of work-related training.

The picture is not great. Over many years governments have sought to influence employers’ investment, putting the funding into areas which hold individuals back from effective performance such as fundamental basic skill levels. The key directions have been to:

- remediate so that employers do not have to invest in the basics that compulsory education should provide;

- raise achievement in education and encouraging progression to higher levels of study to improve the pipeline of skills employers have access to, and

- redefine so that employers define occupational training standards to meet their needs.

There is little to argue with though it could be said that these policy endeavours have led to a continual process of remodelling – new initiatives are implemented to respond to the failures of past ones. While aiming to raise the ‘water table’ of skills, evidence of increasing employer engagement in training is hard to find and instead displacement emerges.

A classic example of this was when Train to Gain closed and apprenticeship numbers soared as the new funded provision, although they were not necessarily focused on those needing new skills to perform their jobs. Similarly, the introduction of the Apprenticeship Levy led employers to take up Degree Apprenticeships for higher education qualifications they previously funded.

As greater value is placed on “problem solving/decision making, critical thinking/analysis, communication, collaboration, creativity and innovation” as the transferable skills most needed over the next 15 years (NFER, 2022), lifelong work-related learning becomes ever more important.

With the plethora of funding schemes and training initiatives, new support to improve navigation of the system are needed as well as provision suitable for adult re/upskilling.

Recommendation 1

Levy and non-levy payers should have greater flexibility over use the Apprenticeship Levy, so that unused funds support wider forms of training rather than just apprenticeships and employers can deploy the levy to fund the provision that best suits their employees’ needs.

Recommendation 2

The government should develop short courses or modular formats that offer employers the chance to fill skills gaps within their workforce. More must be done to encourage employers to directly place their employees on Skills Bootcamps but provision should be at Level 2 (beyond construction and green skills) as well as Level 3-5 with components of training at higher levels if this supports progression in work.

Recommendation 3

The government should introduce a new place-based employment and skills brand to connect employers, employees and labour market entrants to the best training options for their needs.

Any views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Institute as a whole.