EU immigration: impacts and prospects for the UK labour market

26 Aug 2016

Sophie Hedges, Research Economist

Sophie Hedges, Research Economist

As the implications of Brexit unfold and debates about controlling immigration via an Australian-style points-based system roll on, IES looks at the evidence regarding the impact of EU immigration on UK employment levels and wages.

What do recent trends tell us?

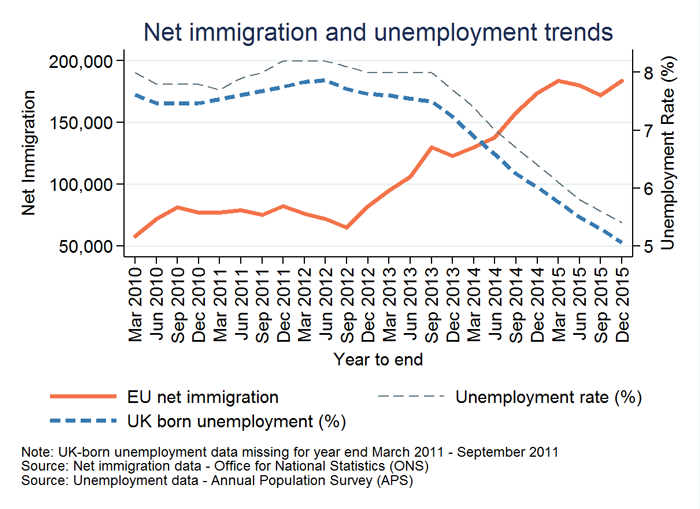

Net immigration from the EU [1] has risen over the past five years. Since 2011, the UK unemployment rate has fallen and the unemployment rate for those born in the UK has remained below the national average. Both of these trends coincide with economic recovery after the recession: unemployment typically falls as the labour market recovers and this may simply reflect a phase of the business cycle. This phase also typically involves a rise in GDP, which has indeed been increasing over this five-year time period, and so the increase in net migration can also be attributed to this: economic migrants follow economic opportunities, so in a period of growth economic migration will increase. So overall these data do not suggest that EU nationals are taking jobs at the expense of UK-born workers in recent economic conditions, but that the economy is expanding and creating the need for more jobs, some of which are being filled by EU workers.

So what about ‘British jobs for British workers’?

A net inflow of immigrants increases labour supply, so a common concern is that this will result in fewer jobs available for UK-born citizens. However, this assumes that:

a) the number of available jobs is fixed, and

b) UK citizens are not emigrating (and hence leaving the UK labour market) at the same rate.

It’s true that emigration figures are lower than immigration figures, but the ‘lump of labour’ argument that there is a set amount of work required in a given economy is debatable. For example, a recent report by the Centre for Economic Performance claims that immigration raises labour demand as new residents consume local goods and services, thereby creating job opportunities. This study finds no significantly negative (or positive) effect on employment. If foreign-born workers are not directly competing for jobs with natives, and are instead creating opportunities and filling roles where there is a relative shortage of UK workers available, then immigration could make a positive contribution to labour market functioning. Furthermore, Wadsworth points out that EU immigrants are typically more highly educated than UK natives, as well as younger, healthier, and more likely to be in employment. He suggests that they are more likely to be competing with existing migrants at the top end of the skills distribution, and any increased competition for work between EU migrants and British workers will be concentrated among people with low skill levels, in specific sectors, and in local labour markets.

Does EU immigration lower wage levels?

An increased supply of labour is expected to reduce wage levels. People are more likely to accept a lower wage when they perceive a lot of competition for jobs, and firms are more likely to offer a lower wage when they have large numbers of similar applicants. The evidence is more mixed on this question than for employment levels. Manacorda et al argue that immigrant workers are not perfect substitutes for UK-born workers. They claim that immigration has no statistically significant impact on the wages of UK natives but reduces immigrant wage levels. In contrast, a recent report from the Bank of England finds a small negative impact on wages, which varies by occupation and skill level, with low-skilled workers taking the biggest hit. Similarly, Dustmann et al argue that average wages were slightly higher as a result of immigration between 1997 and 2005, but highlight that wages at the lower end of the distribution were lower.

Implications of a points-based system for EU migration to the UK

Overall, there appears to be a limited effect of EU immigration on employment and wages, but it is likely to have disproportionately affected low-skilled groups among UK-born workers, and potentially also among previous waves of migrants. It’s probably no coincidence that these low-skilled groups were the most likely to have voted ‘Leave’ in the recent EU referendum. However, it is clear that EU migrants have filled key labour and skills shortages over the years, at both the high and low skilled ends of the labour market, often in key sectors of the economy. For example, Eastern European migrants are known to be concentrated in areas of the service sector, such as hospitality, tourism and healthcare, which contributes to 79 per cent of GDP. Additionally, there are lots of highly skilled EU migrants in finance, another sector on which the UK is dependent.

A popular idea during the lead-up to, and immediate aftermath of, the referendum is that of an ‘Australian-style points-based system’. This system allocates points to visa applicants primarily based on their qualifications and occupation, so that highly-skilled migrants and those which will fill labour shortages are favoured in terms of admittance. Whilst Australia is being looked to as the prime example, some recent papers suggest that it may have flaws, primarily that it relies on the judgement of the government as to which skills are valuable rather than the views of employers. Importantly, a points-based system along the Australian model will not necessarily reduce net migration to the UK. Net immigration in Australia, which is aiming for population growth, is three times that of the UK (proportionate to their population), whereas the UK government has previously committed to a reduction in net migration. Therefore any points-based system would have to be created specifically for UK policy aims, whether that be a reduction in net migration, or filling labour and skill shortages. It is unlikely that both aims will be fulfilled under one system as long as some key sectors continue to be heavily dependent on migrant workers, from both the EU and outside of it. The UK already has a points-based system in place for non-EU migrants, which was introduced in 2008. Under this highly selective system, highly skilled migrants or those whose skills were in demand have been prioritised, and yet there does not appear to have been much of a decline in non-EU net immigration. In the face of Brexit, this system will either be extended to those from the EU or an entirely new system will have to be introduced. Either option could increase competition at the top end of the skills distribution and leave a shortage of workers at the lower end.

What are the options?

There could be at least three options for helping the UK labour market function in response to such changes in labour supply:

a) Policy-makers could seek to improve the chances of low-skilled UK-born workers to fill high-skilled jobs through upskilling. However, the distance to travel in skills acquisition for some people combined with training costs will make this a challenging goal to achieve. The Apprenticeship Levy due to be introduced in April 2017 may go some way towards this, but there would likely need to be further investment in work-based training. Furthermore, there may be a lack of appetite among UK employers for high-skilled employment: the UK has the fourth highest prevalence of qualification mismatch across the OECD countries/economies according to the Survey of Adult Skills, the majority of which is due to workers being overqualified for their roles.

b) Encourage UK citizens to take up low-skilled jobs through a carrot and stick approach. This might involve the carrot of employers paying higher wages or offering improved working conditions as a natural market response to labour shortages, especially for physically or emotionally demanding jobs which are difficult to fill and have high levels of turnover. Whilst employers may be willing to offer improved working conditions, it is likely that measures would have to be introduced in order to incentivise them to raise wages. This could take forms such as wage subsidies; sector-based supplements to the National Living Wage; or the restoration of wages councils, which used to set rates for each sector before they were abolished. The stick approach might involve further reforms to the welfare and benefits system to encourage low-skilled people into work.

c) Reinstate Tier 3 to any ‘new’ points-based system. The UK’s current points-based system used to include a category for low-skilled, non-EU workers to fill temporary labour market shortages. However, this tier was suspended as there proved to be enough low-skilled labour from the European Economic Area (EEA) to fill such gaps. However, if freedom of movement is removed and low-skilled labour from the EU is restricted, then any points-based system would have to re-introduce a tier for low-skilled workers (EU or non-EU) to sustain the low-skilled industries in the UK which depend upon them.

One last point to consider is the possibility of an economic downturn. This would make options (a) and (b) increasingly unlikely because of the additional investment and time needed to upskill and incentivise the UK workforce. Given this, it is likely that Tier 3 may have to be reinstated (at least in the short term) while the UK seeks to reduce its reliance on migrant labour as a more longer term policy goal.

IES will be tracking labour market changes as a consequence of Brexit over the months to come. If you’d like to find out more, do get in touch: sophie.hedges@employment-studies.co.uk

Any views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Institute as a whole.