The 'Great Resignation': is the grass always greener?

2 Jun 2023

Stephen Bevan, Principal Associate

Since 1984 I have conducted more than 40 staff retention studies for employers and I’ve written many reports, articles, chapters and management guides on the topic. I've been interested in the psychology of the decision to quit and what, if anything, employers can do to influence people to stay. Although my research has looked at a wide range of occupations - from soldiers to nurses, accountants and postal workers to insurance clerks, agricultural workers to tax collectors, there is a reliable core of factors which drive the decision to resign regardless of sector. And my hunch is that, despite the hype about the so-called ‘Great Resignation’, these fundamentals won’t have changed very much.

At its most basic, the decision to quit is usually influenced by a combination of 'push' and 'pull' factors[1]. The 'push' factors tend to be drivers within the control of the employer which cause the employee to look for alternative employment. These can include low job satisfaction, disillusionment with career prospects, limited access to training and development, a poor relationship with a line manager or unsatisfactory work-life balance. Interestingly, dissatisfaction with pay is only rarely a major factor (most people feel they are worth a little more money) although the intensity of the cost of living crisis today may mean that more people than normal will be leaving jobs they really like to achieve more financial ‘headroom’. Among the 'pull' factors are a buoyant labour market (plenty of alternative jobs), opportunities for progression or more responsibility, and the chance to gain more experience in a bigger role. I found that, in most cases, that the pay hike leavers get once they quit is the outcome of the decision to leave rather than its cause - which partly explains why retention bonuses rarely work for long.

The main lesson for employers from all of this work is that 'hand wringing' about rates of pay or the state of the labour market are mostly pointless (though, paradoxically, competitive pay can help recruitment once people have decided to leave) and that a laser focus on the 'push' factors over which they exercise greater control is much more likely to deliver results.

Despite the simple logic of this position, I have worked with some employers who were convinced that staff who had the temerity to leave them would soon experience a form of 'buyer's remorse' as they were hit by the realisation that the grass is not always greener on the other side of the fence. On a couple of occasions I have had the opportunity to test this theory and what follows is a brief account of one study which collected data from both stayers and leavers. The results may (or may not) surprise you.

The employer was a large professional services firm which was concerned about two types of retention risk. The first was graduates who had just passed their first significant set of professional exams and the second was mid-career professionals who were in their first managerial roles. Voluntary resignation rates in these two groups were worryingly high given how much the firm had spent on recruiting and training these highly competent people and their potential value to competitors. I was commissioned to carry out a study which followed these leavers (as part of the firm's alumni scheme) and compare their attitudes and experiences to those who had chosen to stay. Senior management, it seemed to me at the time, were keen to show that the experiences of leavers was not as rosy as they had hoped and that staying with the firm for longer was the only rational choice.

Using surveys among 1600 alumni and a sample of 1400 existing staff, I collected data on a range of 'push' and 'pull' factors and compared the two to identify the key differences between the groups and to gather the retrospective views of leavers of their time since leaving the firm, sometimes up to five years previously.

The results, it transpired, showed almost no 'buyer's remorse' among the leavers. Most had gone to work in smaller firms (doing the same work) and were finding the greater autonomy and responsibility more rewarding than being part of a larger operation. The data gave me some fascinating extra insights into why this group had resigned in the first place and the extent to which concern about similar factors might be simmering risk factors among my second sample of existing staff, representing a ‘latent’ turnover problem which would need to be monitored and managed.

Among the leavers (alumni) four in five reflected that the original employer (’the firm’) was generally a good employer and over 90 per cent felt that working there had enhanced their CV and helped their marketability and future career prospects. However fewer than one in five felt that the organisation they first joined after quitting the firm was a worse employer in any significant way. Over 40 per cent of these leavers also reported that they had received two or three promotions since leaving the firm.

We found that most leavers felt that some of the expectations they had on joining the original firm had been artificially inflated by the recruitment process they had been through and a tendency to oversell the firms and its jobs This mismatch between expectations and reality had contributed to a drop in job satisfaction. The biggest gaps were: career opportunities, training and development opportunities, organisational culture, the type and quality of work and the quality of management. We asked about the ‘push’ and ‘pull’ factors which had been the most important in driving their decision to leave the firm. The top three ‘push’ factors were: the nature of the work and job satisfaction, management style and a lack of promotion and career opportunities. The top three ‘pull’ factors were; the nature of the work and job satisfaction, career development opportunities in the new job and the challenges offered in the new job.

Although about 40 per cent of leavers said they might consider returning to work for the firm at some point in the future, the vast majority had no regrets about leaving and forging their careers elsewhere.

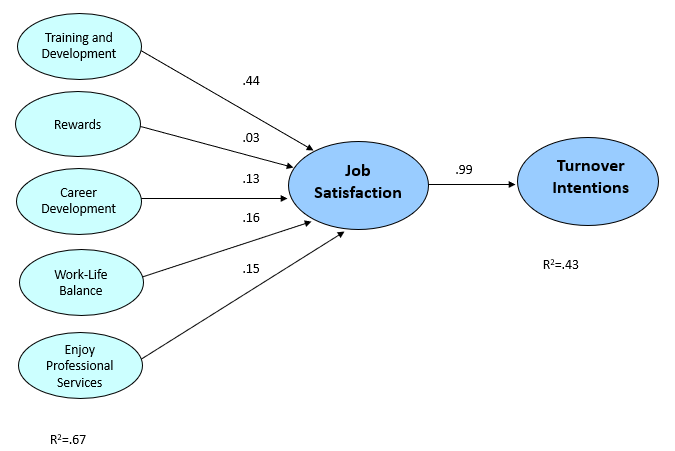

The next question we addressed was that of ‘latent’ turnover amongst the current staff that the firm employed. Could our data shed any light on the factors which might prompt some of this group to consider leaving in the future especially if the same ‘push’ and ‘pull’ factors were important to them? The first thing we did was to try to isolate the main drivers of overall job satisfaction for this group. We used cluster and factor analysis to identify 5 main areas of experience which were statistically linked to job satisfaction (see Figure 1). They were, in order of priority: opportunities for training and development, work life balance, enjoyment of professional services work, career development and rewards. It is worth noting that these five factors explained 62 per cent of the overall variance in job satisfaction for these stayers. So, our analysis captured a big part of the ‘morale’ story for this group.

Figure 1

The presence of both training and development and career opportunities as important factors on this list emphasises how important the issues of development growth and progression were too. Next, we asked how much any dissatisfaction with any of these five domains and with job satisfaction as a whole might be linked to the measure of intention to leave we had used in our survey. Here we found that job satisfaction as a whole explained 43 per cent of the variance in intention to leave but that neither dissatisfaction with work life balance or reward were directly or strongly correlated with intention to leave itself. The message here was that, to keep their current staff, issues of job content, learning development and progression were most likely to be the main ones on which to focus.

Overall, the data confirmed the robustness of the 'push' and 'pull' framework and, crucially for this business, undermined their frankly optimistic theory that the alumni data would show that the grass was by no means greener on the other side of the fence.

As a result of this assignment I recommended a range of actions to improve the firm's readiness for future retention crises. These included a review of the expectations they raised during graduate recruitment, a reassessment of the management of early careers, access to training and development for ambitious and talented employees, a review of the role of line managers in supporting career development and an examination of the intrinsic motivators and job design in early career posts in the firm.

Building on this kind of project experience, the Institute for Employment Studies (IES) has developed and field-tested a number of different retention tools for employers including an exit interview methodology, leavers and stayers questionnaires, a checklist for estimating the direct and indirect cost of turnover, a risk analysis tool for assessing resignation risks in a team and methods to build labour turnover estimates and scenarios into workforce plans and succession plans.

Despite the rhetoric surrounding the so-called ‘Great Resignation’, our experience is that staff retention is often a manageable problem if an employer has good data, an understanding of what motivates its workforce and a willingness to take a systematic and evidence-based approach. For further details of how IES can help your organisation, or to chat about our wider experiences of retention research, please contact Dan Lucy.

[1] Back in in 1958, in their landmark book ‘Organizations’, James March & Herbert Simon suggested that the resignation decision was based on a combination of ‘the perceived ease of movement and the perceived desirability of movement’.

Any views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Institute as a whole.