Planning and preparing for later life in uncertain times

18 Feb 2019

Rosie Gloster, Senior Research Fellow, Insitute for Employment Studies and

Daniela Silcock, Head of Policy Research, Pensions Policy Institute

We know that the UK’s working population is ageing: the proportion of the population aged between 50 and the state pension age is predicted to increase from 26 per cent in 2012 to 35 per cent by 2050, representing approximately eight million people. The number of employees aged 65 and over has also increased: there were 1.19 million people aged 65 and over in work in the period May to July 2016, compared to 609,000 in the same period a decade earlier.

Alongside this, the pensions world has changed dramatically over the last few years as a result of three factors:

Demographic changes

-

People are living for longer and having fewer children.

Market changes

-

The provision of traditional Defined Benefit (DB) pensions has declined in the private sector and most active private sector savers are in Defined Contribution (DC) schemes.

Policy changes

-

Eligible employees are now automatically enrolled into workplace pension schemes and the requirement to buy a secure retirement income product in order to access DC savings has been removed.

Employment legislation such as the extension of the right to request flexible working has enabled employees to taper their working hours and work flexibly into their retirement. Combined with pensions changes, this has been said to have created a ‘period of uncertainty’ between when work ends and retirement begins.

The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) has just published a report investigating the feasibility of a survey about planning and preparing for later life. It summarises our work with NatCen Social Research looking at what information the DWP and its stakeholders need in this area, and what the research programme collecting this information should look like. So what do we need to know?

What should we know about planning and preparing for later life and pensions?

Pension changes mean that more people are saving in workplace pension schemes in which the majority of market risks are borne by the individual member and that those accessing DC saving need to make complex decisions about how to draw an income. It is now extremely important that there is information available to policymakers about how people are behaving in the new pensions landscape, so that potential risks to retirement outcomes (for example, projected increases in poverty) can be identified and dealt with. While there are currently some surveys on the financial behaviour of people in the lead up to and during retirement, there is no comprehensive dataset available which would allow policymakers to draw firm conclusions regarding the emotional, psychological, economic and policy factors which contribute to the way that people behave.

More information would be very useful on the decisions that people make regarding:

-

saving during working life, in particular why people decide to remain automatically enrolled or opt out;

-

why people contribute at the minimum required contribution level or decide to contribute more; and

-

what overall plans people make regarding how to save for retirement.

It is also crucial to understand what people believe they may need, or want to live on in retirement, and what, if anything, they are doing to achieve these aims.

The decisions that people make at and during retirement have a substantial effect on their standard of living throughout the rest of their life. These decisions also affect their ability to cover unexpected changes in need arising from, for example divorce, bereavement or the need for care. Here, we also require greater understanding of how and why people make decisions regarding accessing DC pension savings, to what degree advice and guidance affects these decisions, and whether the decisions that people make prove to have been good decisions in the light of individual’s later retirement experiences.

Alongside information on people’s private pension behaviours, information on people’s attitudes towards the State Pension would help policymakers better understand motivations. The State Pension pays out a large proportion of people’s retirement incomes, so people’s understanding of how much they will receive from it, what they need to do to accrue entitlement, and when they will be eligible to claim their it will have a substantial impact on the decisions they make in planning and preparing for later life.

How does this all relate to employment?

Historically, research into the area of planning and preparing for later life has been divided into topics related to either pensions or employment. Yet, to understand how individuals’ choices are affected by legislation, employment context, and personal preferences and circumstances, surely we need to consider these two concepts together?

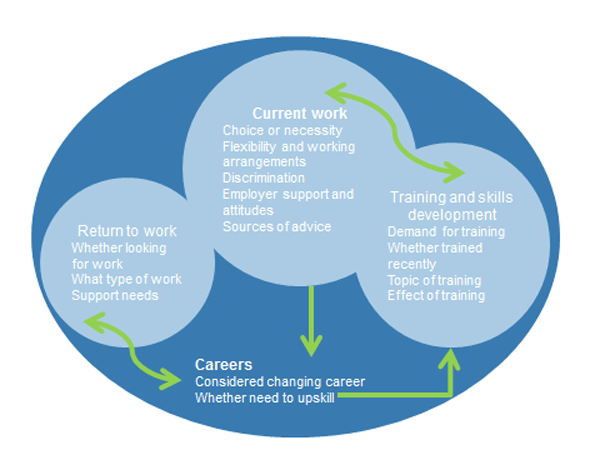

Fuller Working Lives noted that, to encourage a situation where individuals are enabled to stay in work for longer, we need to understand retirement decision-making, the reasons for retiring and things that would have allowed people to stay in work for longer. How employment practices affect the retention of individuals in work also needs to be understood. Figure 1 illustrates the interlinked topics of interest relating to employment articulated by DWP and its stakeholders.

Figure 1: Employment information needs

The current state and private pension systems are designed to provide people with the tools needed to provide themselves with an adequate income in retirement. But some people need assistance to navigate these systems in a way which produces the best outcomes. It is vital that there is data and evidence available to support those responsible for monitoring the success of the pension system and intervening to help those most in need.

In creating a research programme that can robustly inform the development of policy and practice to support an ageing workforce, there is a need for a coordinated response, rather than addressing issues in isolation.

We need to explore the areas discussed above together – for the same individuals and in the context of broad social and financial situations – and discover how the attitudes and circumstances of individuals interlink with behaviour.

The Planning and Preparing for Later Life report sets out how these questions might best be answered. Our colleague, Mari Toomse-Smith, has blogged for Natcen Social Research on how a survey might be a great start.

Any views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Institute as a whole.