Sickness absence falls, but is there a sting in the tail?

1 Aug 2018

Jim Hillage, Director of Employment Policy Research

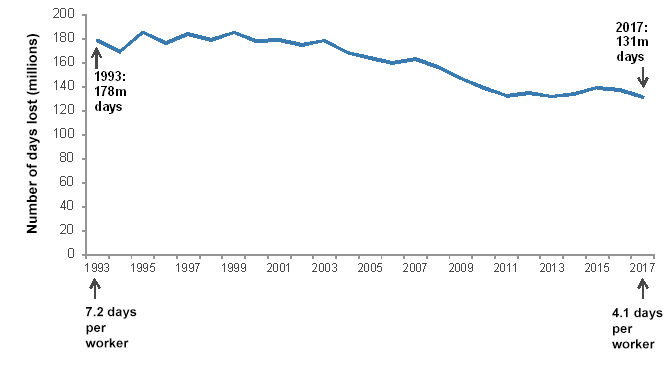

Sickness absence levels in the UK have fallen to historically low levels according to the latest data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS), drawn from the Labour Force Survey (LFS). As the chart shows, days lost in the UK due to sickness absence have fallen from 178 to 131 million over the last 24 years. Given the rise in the working population, the fall in the average number of days per worker has been even more dramatic (7.2 to 4.1 days per worker).

It is not supposed to be like this. In the past there was thought to be an inverse relationship between unemployment and sickness absence. That is, as unemployment rose, absence fell, as employees felt under more pressure to be at work and keep their job safe. Conversely, as employment rose, they felt more able to have the odd day or two off work.

In recent years, the reverse seems to have been the case. Employment rates are breaking records at the same time as sickness absence rates have steadied and this year reached a new low.

So, what has happened?

It is difficult to identify a single reason for the changing pattern. Generally, the characteristics of sickness absence have remained broadly the same over the years, with lower sickness rates in smaller workplaces, among men and among younger people. The latter two points are particularly interesting as there are increasing numbers of women and older people in the workplace and, all things being equal, this would suggest a rise in average sickness rates.

Sickness absence in the private sector continues to be lower than that in the public sector, but this is likely to be due in part to a size effect as public employers are generally larger than their private sector counterparts. Larger workplaces are, for instance, more likely to provide sick pay.

Undoubtedly, one factor is industrial change leading to a decline in the number of manual jobs in more hazardous production industries and the rise of physically less-demanding jobs in professional and semi-professional jobs in services. However, the highest rates of absence are currently found among those in caring, leisure and cleaning occupations, some of the fastest growing areas of work.

Also, the data do not indicate much of a change in the nature of sickness absence. Back pain and other forms of musculoskeletal conditions still account for the largest proportion of days lost and there are few indications of a rise in mental ill-health as a reason for sickness absence, despite anecdotal reports of rising rates of stress and depression. Other sources of data, such as fit notes, however, suggest that the LFS may under-record mental health conditions.

What else has changed?

Employers may be managing sickness absence better and there is a growing awareness of managing health and wellbeing in the workplace and the importance of preventative measures. For over 20 years, IES has been working with employers to help them identify the costs of absence and how best to help people back to work. There have also been a number of initiatives from government, such as the introduction of the fit note in 2010 and, most recently, the Fit for Work Service, on which our evaluation has just been published. The combination of better workplace management and better external support may mean that long-term absences are handled more effectively, bringing down the average, although there is, as yet, little evidence to support such a contention.

However, all these points still don’t seem to add up to a full explanation.

There is one other factor, cited by ONS itself, and that is a rise in presenteeism, ie people coming to work when they are ill. This is a difficult concept to measure objectively and most of the available evidence is anecdotal. For example, according to the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD), 86 per cent of respondents to a recent survey said that they had observed presenteeism in their organisation over the last 12 months, compared with 72 per cent in 2016 and just 26 per cent in 2010.

However, there may be reasons why more employees are turning up for work when they are not fully fit, or indeed working from home when previously they would have to sign in sick. They may feel a professional duty towards the people they look after, such as in the growing care, welfare or educational sectors. They may have concerns for colleagues’ workloads; or be influenced by managers’ and supervisors’ behaviour, or working cultures to demonstrate organisational commitment. Employment policies and economic factors such as fixed-term contracts, absence policies, sickness benefit, bonuses/incentives, and working-time arrangements can also be important. Our own review of the academic literature shows that the greater the extent to which employees feel insecure at work, the more likely they are to feel the need to turn up when ill.

In theory, it could be expected that a decline in sickness absence could be associated with rises in productivity, as there are more productive days available per worker. However, despite high employment rates and low sickness rates, that does not appear to be the case. The sting in the tail, therefore, is that while there may be more workers working more days, they are not producing that much more overall, and UK productivity remains stubbornly low. But that’s a subject for another blog.

[1] A day is defined as 7.5 hours.

[2] The number of days lost through sickness absence is calculated for all people in employment aged 16 and over. The average number of days lost to sickness per worker is calculated by dividing the total number of days lost to sickness by the total number of people aged 16 and over in employment.

Any views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Institute as a whole.