The labour market past and future: fifty years of IES insights

31 May 2018

Jim Hillage, Director of Employment Policy Research

For 50 years, the Institute for Employment Studies (formerly the Institute of Manpower Studies), has monitored trends and developments across employment and human resource management. In 1968, when the Institute was founded, the UK labour market was very different from what we see now.

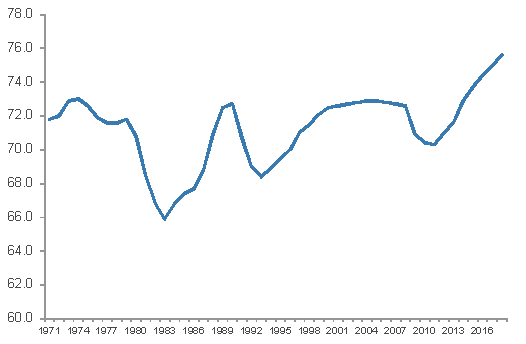

Few people would have predicted back in 1968 that the number of people in jobs in the UK would rise by almost 40 per cent over the subsequent 50 years, from just over 23 million to 32,250,000 at the beginning of 2018. The expansion in employment reflects a number of factors: a growing population (up from around 52 million in the late 1960s, to over 66 million now, partly due to net migration); lower current levels of unemployment; and higher levels of economic activity. These factors mean that the overall employment rate, ie the proportion of the potential working population in work, has not risen as dramatically over the period as the total number employed. That said, it is still up from 71.8 per cent in 1971 to the current record level of 75.6 per cent, as the chart below shows.

Employment rate (aged 16 to 64, seasonally adjusted), UK, May 2018

Source: Office for National Statistics, UK labour market: May 2018

Below these headline figures are a myriad of other trends which, in their own ways, are more interesting and dramatic. These include:

-

a significant rise in female employment;

-

lower employment levels among young people as more stay on in education;

-

initially falling, and more recently rising, employment participation rates among older people;

-

more people working part-time, although, other forms of flexible working are broadly static; and

-

dramatic shifts in the sectors where people are employed, the jobs that they do and the skills that they need.

Looking forward, are these trends likely to continue, or will others arise and become more significant? It is tough making predictions, especially about the future (as American baseball manager Yogi Berra is reported to have said). In 1984, Charles Handy foretold the end of full employment or, at least, the end of the ‘traditional job’ and predicted greater leisure time for all [1]. A decade later Jeremy Rifkin, in The End of Work argued that the information age would also result in a reduced demand for conventional work. Neither turned out to be true, at least in headline terms.

So, maybe predictions aren’t all that helpful. However, we can learn from the past to make some informed judgements about future employment trends, by identifying some of the key underlying factors that influence both the demand and supply sides of the labour market. As an example, in 2010, the then government published the first national skills audit for England, to which IES contributed much of the background research. It identified the key drivers of the employment change. Some are likely to have more short-term effects on the volume of employment while others, such as technology, demography and globalisation have more structural and long-term impacts.

Technology is one of those most-influential factors and the sustained pace of technological change is likely to continue to affect the nature, if not the volume, of employment. Developments such as Artificial Intelligence and robotics are more likely to alter jobs than to eliminate them as many of the more apocalyptic commentaries suggest. The OECD recently concluded that:

-

Lower skilled routine jobs are most at risk of being replaced by automation and ones involving creativity, complex reasoning and adaptation to variable contexts are least under threat.

-

New technology itself creates new jobs, not just in the development and use of the technology itself but also by enabling new ways of working and new services to be created.

Demographic factors are also an important influence and it is highly likely that average working ages will continue to grow and retirement become a more blurred and varied concept, for example with the growing incidence of ‘unretirement’, when people go back to work after a period of supposed retirement.

The impact of globalisation is even more difficult to foretell, especially in the UK, as the nature of our future international economic relationships crucially depend on the post-Brexit settlement and subsequent trade deals. However, it is likely that the labour market will continue to become more mobile, more diverse and, as a result, more complex.

These and many other influences on the 21st century workplace are reviewed in a recent book by IES’ Stephen Bevan, Zofia Bajorek and others, based on the latest empirical evidence. It is that evidence base, one that IES has played a substantial role in creating over the last 50 years, which is crucial to understanding what has happened in the past and thereby making most sense about what will happen in the future.

Any views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Institute as a whole.