Creating system change: bringing services together to facilitate employment - lessons from the Advancement Network Prototypes

2 Nov 2022

Becci Newton, Director, Public Policy Research

Rosie Gloster, Principal Research Fellow

As the IES labour market statistical analysis shows, we are facing a substantial mismatch between labour demand and labour supply. Unemployment is low, but economic inactivity is high, particularly among the over 50s and not simply for reasons of ill health. Alongside this there are 1.2 million unfilled vacancies. Our population is ageing and consequently we need longer, healthier and more productive working lives to maintain our society. Automation, new technologies and climate change are changing the world of work and occupational structures. These factors combine to highlight the importance of re-engaging those who have exited the labour market and better equip people for the changing nature of employment. To do this, the current system needs to adapt to better support people and a focus is needed on how services across employment, skills and careers can better enable more people to find and crucially progress in work.

Recent initiatives, such as Youth Hubs, and No Wrong Door, have sought to join-up services for groups of young people at a local level to good effect. However, this is not a new concept. At the end of the last Labour government, John Denham set out a vision for adults to be able to receive wide-ranging advice to support their needs and enable them to develop their working life in ways that would lead to greater personal satisfaction and productivity. This was to be achieved by joining up employment, careers, skills services, and beyond to wider services, such as housing and mental health support. The result was ten Advancement Prototypes to develop and test local holistic solutions to support adults in their communities. Revisiting the evaluation illustrates how many of the lessons remain relevant today as solutions are needed to ensure support is accessible, easy to navigate and effectively provides support for better, healthier and productive working lives, regardless of people’s circumstances.

How did the systems work?

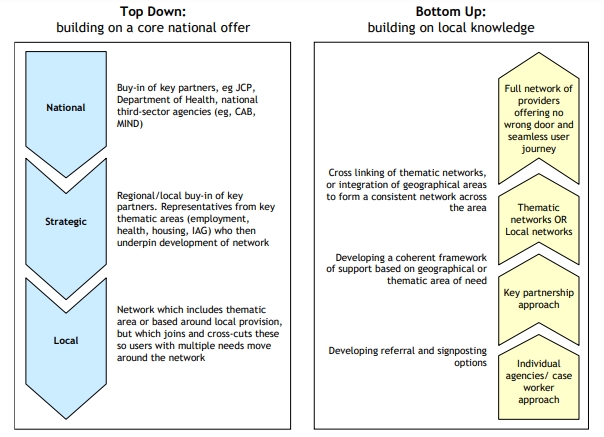

Partnership and network development was at the core of the Prototypes; an element that is often unfunded in project-based commissioning. There were two types of network-building approaches: top down, building on a national core offer, and bottom up, building on local knowledge.

There was understanding that advancement would mean different things for different people; and that each person’s situation and context was different. Eligibility for support was not linked to receipt of benefits or applying for a specified number of jobs each week. Instead, the approach was person-centred; with individuals deciding what work should look like for them and building towards that goal. Through networked approaches, the Prototypes:

- Made better use of existing resources by developing diagnostic tools and directories of local services; setting out procedures to support inter-agency working, such as the development of a network quality standard; and awareness of local organisations and encouraging client referrals.

- Engaged with new clients through trusted, often third sector, organisations. The clients engaged through outreach did not ordinarily seek support from mainstream services; and

- supported clients not ready to access mainstream services, where the networks offered a significant depth of service to people to improve their capacity to engage with mainstream services in the future.

Working across employment, skills and careers had benefits for services and service users

There were positives from the collaborative working models established for delivery organisations. These included:

- Increased knowledge of other local support services that could help their clients, making staff better placed to refer clients.

- Organisations being able to play to their strengths and use specialist support in the network to enhance and improve the offer to clients.

- Being able to identify and help people who would not ordinarily engage with mainstream employment and skills provision, such as the Jobcentre.

- Utilising the skills, experience, and resources of local public, third and private sector bodies some of which were not previously engaged in employability programmes.

People who accessed support from the Prototypes said they received a tailored and personalised service and had access to a better breadth of support than they would have from mainstream services. As a result of the support received, their confidence increased, and they felt better equipped to manage their work situations.

Nonetheless, it was not all plain sailing and establishing support networks met with challenges. It was critical to have a common vision and purpose, minimising duplication and creating collaborative advantage. The credibility of the lead organisation was central in ensuring wider buy-in. As project-based funding came and went, networks needed to be adaptive, finding ways to fill gaps. This contributed to issues for sustainability. There is a need to recognise that networks and partnerships require investment, not just to set-up, but also to adapt and maintain momentum.

Thinking more broadly about the determinants of employment and the support people require, informed by earlier attempts, will help to make services work more effectively and bring benefits for individuals, organisations and to help overcome our current labour market challenges. The new structures that have been implemented since the Prototypes, including devolution and combined authorities, and initiatives to link local economic development and skills such as local skills improvement plans suggest new opportunity to build local brands to connect people with sustainable and fulfilling employment.

Any views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Institute as a whole.